We are almost there! I imagine most of you reading this are beginning to see light at the end of tunnel that is winter break. If you are like me this also means you are ridiculously busy with all the end of term business: finals, review sessions, grading, etc. If you are feeling the stress of the last push of the semester take a deep breath, and take a moment to relax by reading some funny, but maybe a bit too real, comics. Now that we all are still stressed, but well oxygenated, let’s get down to brass tacks. I want to talk about another end of semester ritual that often goes undiscussed: teaching evaluations.

This semester I was part of a committee that reviews teaching evaluations. It has been a very interesting experience that has included reading thousands of student comments, and has given me the opportunity to think more about the advantages and limitations of teaching evaluations. In doing so I keep returning to the following truism of human nature:

How we perceive the world around us is influenced by our conscious and unconscious biases.

In particular, the words we use to describe people are often shaped, consciously and not, by the gender, race, ethnicity, and other characteristics of that person. This applies to teaching evaluations just as it applies to (essentially) everything in life. So unlike what we might at times pretend, teaching evaluations are not an accurate depiction of the truth. They offer a version of the truth distorted through the prism of gender, race, etc.

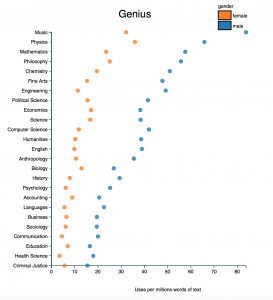

Consider this awesome interactive chart created by Ben Schmidt that allows you to see how frequently various words are used in RateMyProfessor reviews by gender and field. So for example, if you search the word “genius” we see that in every field, but especially math, it is much more frequently used in the reviews of male instructors as apposed to those of female instructors.

Number of student comments on RateMyProfessor using the word “genius” broken down by discipline and gender of professor.

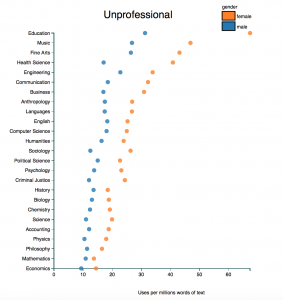

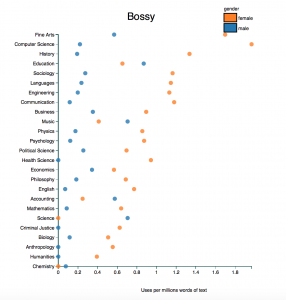

On the other hand reviews for female instructors are much more likely to use the words “unprofessional” or “bossy”

Of course this chart has its limitations, see here for a discussion of some, however, the picture painted by this is stark. Are female mathematicians really substantially less likely to be “genius” compared to their male counterparts? Or more unprofessional? Or more bossy? (Hint: The answers all begin with “Of course” and end with “freaking not”.)

This is made more striking when we acknowledge the large body of scholarly work showing the existence of gender bias in teaching evaluations. Consider the following experiment: Two teaching assistants (TA’s), one female (Alice) and one male (Bob), each teach two online sections of an introductory anthropology course at a large public institution. For one of their sections, each TA teaches as they normally would while in the other section they take on the persona of the other TA. So in one of Alice’s sections the students believe their TA is named Alice while in Alice’s other section the students believe their TA is named Bob. Likewise for Bob’s students. (Note: It is important that there was no direct contact between the students and TA’s as everything was done online.) At the end of the semester, the students completed teaching evaluations.

So what were the results? The TA the students thought was female received significantly lower teaching reviews regardless of the TA’s actual gender! As the authors of the study state

“The difference between how students rated the two perceived genders stands in stark contrast to the fact that neither the actual male nor actual female instructor received significantly higher ratings than the other. … Our findings show that the bias we saw here is not a result of gendered behavior on the part of the instructors, but of actual bias on the part of the students. Regardless of actual gender or performance, students rated the perceived female instructor significantly more harshly than the perceived male instructor” [2, pg. 300-301].

So again we see that things we often taken as accurate reflections of the world are in fact not, but are distorted through the lens of gender, race, etc. Some of you might suggest this study has methodological problems – I, for one, am not qualified to make such attacks – but it is not alone. Study after study after study show gender bias exists in how students evaluate instructors.

All of this is not to say we should entirely discount student comments when evaluating teaching. Such a suggestion, in large part, would miss the point:

How we perceive the world around us is influenced by our conscious and unconscious biases.

Whether reading teaching evaluations, hiring and mentoring students, refereeing a paper, or evaluating grant proposals, research quality, or vitae our internal and societal biases affect how we all look at individuals. The important thing is to not discount student comments, heck this post is not really about teaching evaluations, but instead call upon mathematicians to recognize and acknowledge the biases around us, including our own. In recognizing our biases we are able to help understand where our beliefs and feelings truly come from. By acknowledging them we fight to counter our biases and the biases around us to create a more fair and just community.

Acknowledgement: I owe a ton of thanks to all of those who took the time to read various drafts of this post and give their thoughts and suggestions. This piece would not be the same without their generous help. Thanks all!

Bibliography

[1] – Bornmann, Lutz, Rüdiger Mutz, and Hans-Dieter Daniel. “Gender Differences in Grant Peer Review: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Informetrics, The Hirsch Index, 1, no. 3 (July 2007): 226–38. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2007.03.001.

[2] – MacNell, Lillian, Adam Driscoll, and Andrea N. Hunt. “What’s in a Name: Exposing Gender Bias in Student Ratings of Teaching.” Innovative Higher Education 40, no. 4 (December 5, 2014): 291–303. doi:10.1007/s10755-014-9313-4.

[3] – Moss-Racusin, Corinne A., John F. Dovidio, Victoria L. Brescoll, Mark J. Graham, and Jo Handelsman. “Science Faculty’s Subtle Gender Biases Favor Male Students.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, no. 41 (October 9, 2012): 16474–79. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211286109.

[4] – Schmidt, Ben. “Gendered Language in Teaching Reviews.” benschmidt.org/profGender

[5] – Steinpreis, Rhea E., Katie A. Anders, and Dawn Ritzke. “The Impact of Gender on the Review of the Curricula Vitae of Job Applicants and Tenure Candidates: A National Empirical Study.” Sex Roles 41, no. 7–8 (October 1999): 509–28. doi:10.1023/A:1018839203698.

[6] – Tregenza, Tom. “Gender Bias in the Refereeing Process?” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 17, no. 8 (August 1, 2002): 349–50. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02545-4.

[7] – Wenneras, Christine and Agnes Wold. “Nepotism and sexism in peer-review.” Nature 387, (May 22, 1997): 341-343.

Thankyou for the great piece of informative content. I really appreciate your content and efforts. I am sure this is helping tons of people out there just as it helped me. Lots of Best wishes to you. May jesus bless us all.

nvsp tamilyogi matar paneer