If you follow me on social media, you will know that lately I’ve been posting almost exclusively about the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) project that is supposed to be built on/in Mauna Kea on the island of Hawaiʻi. I’ve never blogged about it though.

The main reason I haven’t taken this on is that my writing is inherently selfish and the fight to protect Mauna Kea is not a time for me to be selfish. You see when I blog, I share my experience and I grapple with the burdens of being marginalized. In my home on Oʻahu, though, I grapple with my settler privilege. When I write I am secretly hoping to write something awesome that people will love and share (sorry, not sorry). When I blog, I am demanding space. And in Hawaiʻi, brought in by the University of Hawaiʻi, living in housing subsidized by the University of Hawaiʻi, I am already taking up too much space.

This is not going to be a revolutionary piece on why we should protect Mauna Kea and stand with all indigenous people who fight for their land. They have already said and will continue to say all the most important reasons for their actions. Please educate yourself.

Morning meetings, Mauna Kea, 2019

Photo by: Eric ʻIwakeliʻi Tong

I am writing here because silence is violence, because finding no use for my privilege is a privileged mindset. I write because there are people I can reach, as a non-native, with whom I can communicate, and it is my burden to do so. (Though again, others are better equipped and it is a shame that anyone might be getting their first glimpse of this now.)

Mathematicians need to know that we in academia—especially those of us in STEM—are in the middle of a struggle for our humanity. (Well, humanity has never been what it claimed—much like America has never lived up to its self-image—but let’s just call it humanity.) I do not know the entire history of the TMT project, whose idea it was, or who decided Mauna Kea was the best spot, but I do know that kānaka maoli (Native Hawaiians) had no power in the decision-making process. I know that those who have taken and destroyed so much could never be trusted with a site as precious as Mauna Kea. I use precious instead of sacred, following this definition, because many of us haven’t unpacked our religious bigotry when it comes to how we discuss indigenous beliefs.

The ability to view a mountain as precious is something that colonialism and capitalism has stolen from us.

I’m going to say it again.

The ability to view a mountain as precious is something that colonialism and capitalism has stolen from us.

My first semester at UH, I taught Business Calculus (zero stars, btw, do not recommend). I was supposed to tell my students how to maximize profit by minimizing, among other things, the cost of labor. The cost of labor. Nowhere in my book did it explain that labor was actual people with families to feed. Nowhere in my book did it explain that the cost of labor was how much you paid people who were counting on this money to survive. At no point did it discuss how to know if you were mistreating labor. The idea that you can apply calculus to human lives was taken as a given. And I was supposed to show them how to do it. Even when it’s not Business Calculus, our apolitical abstract lectures perpetuate the idea that there is nothing precious.

Right now, Indigenous people and their settler allies around the world are saying ʻAʻole TMT: No TMT. They are doing this not just because Mauna Kea is precious, not just because it is sacred to Native Hawaiians, but because they know first-hand what happens when their land is taken. We are hundreds of years too late for this kind of favor, hundreds of years and countless lives too late to request this level of trust.

Ihumātao solidarity, police vans in the background, Mauna Kea, 2019

Photo by Eric ʻIwakeliʻi Tong

The mathematics community needs to care about this for many reasons. First, these are our students. One of the barriers to success for marginalized and first generation students is the disconnect between their academic world and their home life. When kūpuna (grandparents, elders) are being arrested, when kānaka maoli have to do the arresting, when Hawaiian scientists are being erased, when Hawaiians opposing construction are being mocked as “backward,” and when all of these degrading interactions are played out in national media, these are aggressions on native people everywhere, and our indigenous students shoulder this burden.

Second, those of us who work at research universities are complicit in the state violence acted upon a community who is explicitly posing no threat. The Governor of Hawaiʻi declared a state of emergency because his interests were being threatened, and the university’s interests are being threatened. He went on TV and attempted to portray non-violent (and frankly, life-affirming) protest as a threat to public safety. This type of action is not necessary if you are doing ethical research, and should not be

supported by anyone in academia. We have to reevaluate what we think our quest for knowledge is worth, and whom we’re willing to force to pay that price. Any argument that only discusses the wonders of discovery can be used, for instance, to experiment on humans without consent.

-

-

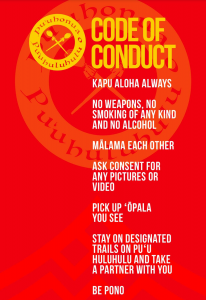

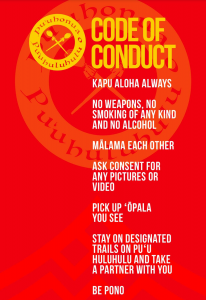

Code of Conduct, Mauna Kea, 2019

-

-

Schedule of Classes, Mauna Kea, 2019

Lastly, all of this ties back into something we’ve discussed here before, namely humanizing mathematics. From recognizing the humanity in our own students, to recognizing science and math as human endeavors, we must break free from this colonized/capitalist metric that sees humanity as a distraction. Indigenous voices, history, and knowledge will be essential to decolonization and sustainability. The time to start listening is long, long, overdue.

A scene from the workshops

(Puʻuhuluhulu University)

Photo by: Eric ʻIwakeliʻi Tong

I will close with something personal because as valuable as abstract reasoning can be, it doesn’t matter if it isn’t personal.

The first people I met on Oʻahu were white moms who were mostly military wives. They had their own community, and I wasn’t sure how they fit into my desire to understand the local culture(s). Turns out, they didn’t. After many months and many hours in traffic spent just to “socialize” my three year old, an entire mom group abruptly cut me out of their lives over a Facebook thread. I had posted a link about white privilege on a thread where they were complaining about Black Lives Matter, and this was too much for them. I was stunned. Not that they were upset, but that they didn’t think it was worth getting through. My only thought was: “How are you going to burn bridges with people when you live on an island?!” It seemed so clear to me that this was an unsustainable attitude. I would later read about Hoʻoponopono, the Hawaiian process of conflict resolution, and this would be my first connection (however loose) with Hawaiian culture.

I never learned as much local history as I wanted. I never got past the second

chapter in my ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi book. I couldn’t figure out the politics of sovereignty,

or remember the right language regarding the US relationship to Hawaii. I wasn’t even

sure if I should be saying aloha and mahalo. Really, the only thing that was immediately

clear to me was that we should definitely not be building an Earth shattering telescope

on pristine land, especially not sacred Earth, especially not stolen land.

Last year was the first time I attended a demonstration about Mauna Kea. I am

embarrassed to admit I was shocked at how much I agreed with what was being said. I

knew I supported kānaka maoli as an ally, but I still had not unpacked my bigotry that doesn’t have a place for “sacred” things. I expected to hear about ancestors and traditional practices, things that have been abstracted away from me without my consent. Instead I heard about sustainability, about accountability, about abuse of power, about mismanagement and lies. At the end of the event I was about ready to stand arm in arm and face the police on the Mauna.

And then they sang.

I have the privilege of being moved without feeling the exploitation. I have the privilege

of wishing I could go to the Mauna for selfish reasons. But I am also a Black American

who longs for that sense of the sacred that racism took from me. While it may seem silly, Black Panther was amazing for me on so many levels—especially when it depicted a society thriving through a mixture of an Indigenous culture and futuristic technology. In school I was told that viewing mountains as sacred was primitive, or, at best, quaint. In school I was taught that we had moved on from valuing nature for how it sustained us, and we were now properly in the era of doing whatever we wanted because we’re so smart and technologically advanced.

It’s 2019, and the United States has concentration camps, and one of my Senators is chairing a Special Committee on the Climate Crisis while his own State was taking police action against some of its most beloved elders because they were breaking with US protocol of legislated desecration of natural environments. It must stop. Mauna a Wākea is my first sacred mountain. It is the first time I have been willing to take a risk for a natural resource. My link to the Mauna is through the kānaka maoli organizing resistance and the kūpuna getting arrested and through the realization that this is the only way forward. It’s 2019, and maybe we’re all going to hell, but if we don’t stop TMT we will be going there a little bit faster.

Kū Kiaʻi Mauna

Kū Kiaʻi Mauna

Kū Kiaʻi Mauna

Mahalo nui loa to Aurora Kagawa-Viviani, Sara Kahanamoku, and Katie Kamelamela for help with this piece.

==============================================================

[Editorial Comment: While this blog and its authors do not speak for the AMS, we hope all readers will take seriously the challenge to think about research as an institution that impacts the world that we often view as outside our explicit inquiry, especially readers who identify primarily as researchers.]

called Race and Gender in the Scientific Community, and I’d like to say some things about what that was like for me. I have the idea that by reflecting on this experience I might manage to breathe a little new life into the overused and inadequate words “diversity and inclusion” for some of the people who read this. I’ll tell the story of the Race and Gender course, and I’ll tell some other personal stories, too. There’s a common theme to this set of narratives: it’s all about learning and changing by paying attention to what people have to say.

called Race and Gender in the Scientific Community, and I’d like to say some things about what that was like for me. I have the idea that by reflecting on this experience I might manage to breathe a little new life into the overused and inadequate words “diversity and inclusion” for some of the people who read this. I’ll tell the story of the Race and Gender course, and I’ll tell some other personal stories, too. There’s a common theme to this set of narratives: it’s all about learning and changing by paying attention to what people have to say.

this post to announce that I have stepped into the role of Editor-in-Chief of this blog. This might raise some questions, and it’s a good time to write a little about how I see the blog, plus we’d like to hear about your ideas.

this post to announce that I have stepped into the role of Editor-in-Chief of this blog. This might raise some questions, and it’s a good time to write a little about how I see the blog, plus we’d like to hear about your ideas. for this important event!

for this important event!

collection of essays entitled

collection of essays entitled  The school year is over, commencement has come and gone, grades are in, and the summer lies ahead of us, with all of its promise of research or rest or travel, and only one potential obstacle looms in the horizon – the dreaded teaching evaluations. We have all been traumatized and scarred by teaching evals at some point in our lives. If you’re in a privileged position like mine, with tenure, chair of your department, and no promotion coming any time soon (I am only eligible to go up for promotion in like three years), you can avoid the trauma using one simple trick: just don’t look, until you have to. You know no one else will, either. But this is not the case for early career tenure-track faculty, postdocs and other visiting faculty, or for “tenure exempt” faculty (Linse, 2017). The fact is that so-called Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) are still heavily used for reappointment and promotion, and sometimes requested by hiring committees. But another fact is that this data could potentially be useful even to senior faculty – for our own teaching but also as colleagues and mentors to these more vulnerable faculty. Last week, I attended a workshop at my institution run by my colleague in Chemistry

The school year is over, commencement has come and gone, grades are in, and the summer lies ahead of us, with all of its promise of research or rest or travel, and only one potential obstacle looms in the horizon – the dreaded teaching evaluations. We have all been traumatized and scarred by teaching evals at some point in our lives. If you’re in a privileged position like mine, with tenure, chair of your department, and no promotion coming any time soon (I am only eligible to go up for promotion in like three years), you can avoid the trauma using one simple trick: just don’t look, until you have to. You know no one else will, either. But this is not the case for early career tenure-track faculty, postdocs and other visiting faculty, or for “tenure exempt” faculty (Linse, 2017). The fact is that so-called Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) are still heavily used for reappointment and promotion, and sometimes requested by hiring committees. But another fact is that this data could potentially be useful even to senior faculty – for our own teaching but also as colleagues and mentors to these more vulnerable faculty. Last week, I attended a workshop at my institution run by my colleague in Chemistry