Why (yet) another article?

There are competing theories online about possible interpretations of John von Neumann’s quote, but manifolds are definitely some mathematics that “you don’t understand … you just get used to them,” — at least for a while.

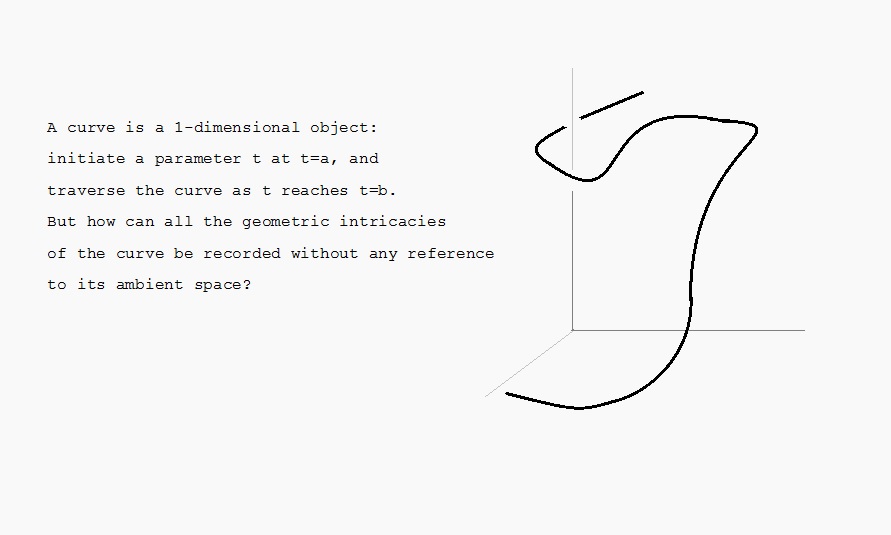

In a series of posts reflecting on my own experience, I will try to motivate the conceptualization of manifolds, and the implications such an abstraction has/had on our understanding of, basically, shapes. I hope to point to some beautiful geometry in low dimensions that you may have passed by too quickly to take notice of.

I must underline the subjective nature of my articles, and that by no means are they meant to narrate the history of the subject, or depict a current fashion in the community. This is simply “another article.”

The first three articles will be dedicated to converting the conventional calculus of curves into manifold language. We will see that a curve can be replaced by an interval endowed with some structure. This will pave the way for an exposition of the theory of surfaces in subsequent articles. The reason for such an extended sequence is to include as much detail and as many examples as possible.

The Question

Diagram by Behnam Esmayli

What We Know from Calculus

From calculus we fix a Cartesian coordinate system for three-space and then parameterize our curve by a map from a subset of ,

If is a smooth parameterization, then the length of the object between two of its points

and

is given by

The curvature is given by

and the torsion is given by

where differentiation is taken coordinate-wise.

Notice that the integral above involves only the length of . Thus, even if we don’t have

itself , but only some

, we will again be able to measure the length of any segment of our curve.

This observation invites a search for a representation of our curves independent of the three-space.

The Answer to the Question

In a search for a 1-dimensional embodiment of a curve, the following theorem is the best we could hope for.

Theorem: Given differentiable real-valued functions ,

and

, with

ranging in an interval

, there is a curve

with

being its curvature and

being its torsion and

giving its length between points. Moreover, any other curve with this description is obtained by changing our origin and rotating the axes rigidly. (See Chapter 1 of do Carmo’s book Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces.)

Thanks to this theorem, an interval along with the following set of data can be thought of as a curve in

:

- A real-valued function

, which will help measure the length,

- A real-valued function

, which will help measure the curvature, and,

- A real-valued function

, which will help measure the torsion.

Note that this data is independent of the specific positioning of our curve in 3-space.

So far…

A curve in is nothing more than an interval in

along with three real-valued functions defined on it! Once we have this set of data, we can forget about our original curve as a subset of

, and work in 1-dimension. After all, we can reconstruct an exact copy of our curve in 3-space from the data whenever we wish.

In the Next Installment…

- We will discuss some constructions, e.g integration on curves, that this description makes possible;

- We will see examples of curves described by a set of data,

- We will find out a way to tell when two sets of data determine the same curve, which will allow for the definition of 1-manifolds in the following article.