Testimonios is a publication by MAA/AMS edited by Pamela E. Harris, Alicia Prieto-Langarica, Vanessa Rivera Quiñones, Luis Sordo Vieira, Rosaura Uscanga, and Andrés R. Vindas Meléndez and illustrated by Ana Valle. It brings together first-person narratives from the vibrant, diverse, and complex Latinx and Hispanic mathematical community. Starting with childhood and family, the authors recount their own particular stories, highlighting their upbringing, education, and career paths. Testimonios seeks to inspire the next generation of Latinx and Hispanic mathematicians by featuring the stories of people like them, holding a mirror up to our own community.

The entire collection of 27 testimonios is available for purchase at the AMS Bookstore. MAA and AMS members can access this e-book for free through their respective member libraries (MAA | AMS). Thanks to the MAA and AMS, we reproduce one chapter per month on inclusion/exclusion to better understand and celebrate the diversity of our mathematical community with folks who are not MAA/AMS members. [The AMS has recently decided to end its blogs, so the future of this effort is unclear.]

From Mexico to Los Angeles

Dr. Erika Tatiana Camacho, Illustration created by Ana Valle.

My dad died when I was three months old leaving my mother to care for me and my three older siblings, ages four, three, and two. This was in Guadalajara, Mexico, where a lack of money meant lack of opportunity. After struggling to raise us by herself for a few years, my mother took up the offer of my grandma (my dad’s mom) to take the four of us in, so that she could focus on working to make ends meet. My grandma lived two hours outside the city and so this also meant that my mom was only able to see us on the weekends. Worse was the fact that my grandma was not a caring person. Behind closed doors, she allowed us to be abused often and it seemed like she just considered us free labor. My mom would give her most of her paychecks thinking that the money was going to our clothes and food but this was not the case.

My mami and I celebrating my oldest sister’s birthday in 2020.

We didn’t have any toys to play with and many times would go hungry. She would also have us sell candy on the street and other things that my mom was not aware of. After a few years, my mom finally caught on and took us back to Guadalajara with her.

When I was seven, she met my future stepdad and corresponded with him for a while. He lived in the U.S. and promised an opportunity for a better life. After nearly a year of correspondence dating, he proposed and we soon moved to the U.S. Unfortunately, he had not been honest about his financial situation and we (my stepdad, mom, me, and my three siblings) first moved in with his adult nephew for a year and then into a one-bedroom apartment in South Central Los Angeles. Life was tough as we didn’t speak English and went straight to English-only school. There are many stories of the rough life we endured for the next year in school, walking to and from school, and around the neighborhood. For example, my brother got stabbed within the first week of getting to the U.S. by two 18-year-old guys who followed us when we were walking from school (all I remember is him telling me and my sisters to run as he thought he would hold them back). After two years, we moved to East Los Angeles with my new baby sister to an equally harsh environment but at least we knew the language since most people spoke Spanish. We remained in East L.A. (in the same two-bedroom apartment) until I was already in college.

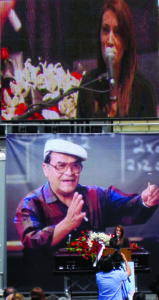

Giving a speech at Jaime Escalante’s (Kimo’s) memorial.

Shaping my dreams—the teachers who inspired me. It was my time in East L.A. that really formed my academics. I could not speak English that well, in part because the language that was still spoken in my house and community was Spanish. In seventh grade, my overcrowded school mistakenly placed me in Honors English instead of English as a Second Language (ESL) class. When I tried to talk to the school counselor, I was told that I should be happy that I was placed anywhere because at least 100 students still did not have a placement. The Honors English teacher, Mrs. Warnock, who noticed that I was not going to get placed in ESL after multiple times of trying, told me that if I was willing to put in the work during lunch and after school that she would spend the extra hours tutoring me. I accepted, did well, and was placed in Honors English from there on (thus, by chance, ensuring that I would have the required classes to apply to a four-year college).

In high school, I was fortunate to have the late Jaime Escalante of Stand and Deliver fame as my math teacher. He was the one that really showed me the power of math and what it can do with hard work. While I was not featured in the movie (it was based on a class ten years before me), the depiction of a tough-love teacher who had Saturday morning math sessions was very precise. Before meeting Jaime, my dream job was to be a cashier. Jaime, or “Kimo’’ as we called him (for Kimo-sabe, the one who knows it all), often brought alumni into the classroom. One of these alumni was a student who went to MIT and worked at a research lab in California. He talked about what engineers can do with math and about the nice car that he drove and the peaceful neighborhood he lived in. What was an old dream changed: I wanted to be an engineer and go to MIT!

College Years and Beyond

Struggling at Wellesley. My high school student government sponsor, Mrs. Dumas, gave me $500 to apply to colleges when she found out from other students I didn’t have the money and thus was not planning to apply to any college that had an application fee. Being too proud, I told her I couldn’t accept it and I only accepted it after she insisted and put the condition that I would not repay it to her but would instead “pay it forward,’’ which is something I feel I have spent much of my life after college doing with numerous students and individuals with similar struggles. I went to Wellesley College for undergraduate school and wanted to be an engineer and take advantage of the joint Wellesley-MIT dual engineering degree program.

In my first physics class at Wellesley, I struggled, partly because of the language, but mainly because of the racism of both the professor and my lab partner. When I went to office hours to ask for help on a particular topic, he started off by asking where I was from, and then after I answered, proceeded to say that he did not understand why they kept letting people like me in while taking a spot from other more qualified applicants.

Celebrating in college with my friends from high school Becky Marquez and Christina Miranda.

During one of my first physics labs, my partner asked if my accent was French because she had been to France a few times. When I told her my accent was because I was Mexican and I came from East L.A., she said that she could not be my partner because I would hurt her grade and she immediately went to talk with the professor. She was promptly reassigned to a new group—everyone was in pairs except her group of three and my group of one. When I asked the professor if I was going to have another lab partner assigned because it was often hard to do the experiments alone, he repeated the same comment he told me in his office hours and said that he could not blame my lab partner for not wanting to work with me. We had not had a single thing graded up to this point, so I internalized this and began to question if I really belonged there. Either by myself or occasionally with a Spanish major friend helping in the late nights when no one else was in the lab, I struggled through the semester. I was devastated by my C grade and realized that my dreams of being an engineer were gone.

I was always very good at and enjoyed math so I decided to be a math major. I had also taken an economics course and really liked it so I double majored with economics too (and econ was one of the few classes in the sciences where the students were always willing to work with me). Even though I was good at both subjects, I still had to work really hard. There were many times when I was ready to quit. One of the hardest parts was not feeling that I could call my mom because her show of support would be to tell me to come back home, leave college, and that one of my sisters could help me get a job.

When I was in this situation, I would sometimes call Kimo. One of the times I called him, I reminded him that he promised me he would get me to MIT but that I was at Wellesley, and things were rough. He livened the moment immediately by telling me that his estimate is not an exact science. He said he did really good by getting me within 50 miles of MIT since Wellesley is just outside of Boston. He also reminded me of why I needed to stay in school. Key mentors, like Kimo, that supported me in critical moments were what helped get me through undergraduate school.

Towards a PhD in mathematics. One of the things that inspired me to pursue my PhD was being able to participate in a summer Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU). It was after this that I decided I wanted to become a professor, and impact students through research and mentoring.

In grad school, I remember studying analysis with a Latino friend and we were thrilled to be taking the class from the only Latino math professor. We did our homework together and I consistently did better than him. When it came to the exam, he scored higher than I did by a letter grade. On the second exam, I again scored a letter grade lower. I went to the professor’s office to go over a few mistakes I made on the exam. The professor took this opportunity to belittle me and to lecture me on how it was important to do my own work and not to cheat. I asked him what he meant and he said that I was clearly copying from my friend’s problem sets since we had about the same homework score but that he scored higher than me on the exams. I was devastated by the accusation. It was hard to sit through the class for the rest of the semester and the following one too (as I had the same professor). What was most disheartening was that my friend in the class confided to me that he had been given the exams from the previous year and that the questions were almost identical. He did not offer this material and I did not ask him to share it with me nor did I ever tell the professor. I just started to distance myself. A year later he asked why I did not want to work or study with him anymore. I told him about what the professor had told me and he laughed and said it was funny that I was accused of this.

During my third year in graduate school I had my first child. My husband was three years ahead of me, and had just graduated. We tried to move back to Los Angeles as he had a job lined up and I thought I would be able to do my research remotely. After a few months of a lack of productivity for numerous reasons, I realized that if I was going to complete my PhD I would need to move back to Ithaca to do it. It was one of the hardest decisions I had to make. However, seared in my mind was my personal upbringing of my mother, who only had a very limited education, working two to three jobs to support her family because you never know what life will throw at you. I wanted to make sure my son was never in that same position and so I moved back to Ithaca and he stayed in L.A. with his dad (and my mom and family). It was a very difficult two years to finish, but I saw no other way to do it. I was so proud to have earned my PhD, but it came at such a high price.

Early experiences as a professor. In my first permanent job, I was struggling with the lack of respect from students in the service courses I taught. I had a student that, upon receiving a well-deserved C on a test, stood up in the middle of class and proclaimed that his tuition paid my salary and that I needed to curve the exam because he needed a B in the course. I told him that he deserved the grade he got but that he could come to office hours and I would help him. He used profanity and told me I would be sorry I gave him a C and that he would go talk to my Chair, which he did. I was then called to my Chair’s office and lectured that I couldn’t tell the students that they deserved a certain grade and that I needed to schedule more time to work with this student than just office hours because those hours did not work for him. Grudgingly, I obliged, but the student rarely kept appointments we scheduled. From then on, he would use profanity when referring to me in the classroom, which my Chair refused to address but instead reminded me that I could not kick the student out or do anything but continue to be polite and teach.

Not much changed my second year, except for my Chair. One day, she called me into her office and said that I needed to stop wearing skirts and bright colored clothes and this was the root of all behavior problems in my classes. She explicitly told me to start wearing suit coats and pants and to make sure they didn’t fit tight and nothing with bright colors. Her basis was one comment in one student evaluation that said he couldn’t concentrate because I was too cute and young to be a professor. Yet she ignored the multiple comments from students who explicitly wrote “send her back to Mexico,’’ “get a professor that knows how to speak English,’’ “we cannot understand her thick accent,’’ etc. and from others to kick the disrespectful kids out of class. I was devastated but found no other choice than to listen.

There have been many times that I have felt like quitting and multiple times, I was one conversation away from just walking away. In looking back, the striking thing is that it was never about mathematics! It was about the climate and culture at a place, stereotypes that people held, subtle and explicit racism, and microaggressions I endured and to which I am still subjected to this day on a regular basis. I think many people believe that academia is a blind place where your talents will be recognized appropriately and where you will not be judged by your looks or other characteristics. But the reality is that academia is made up of people and those people have their biases just like they do everywhere and is one of the most judgmental, inequitable, and political places. Too many people use “merit’’ to cloak discrimination. While I have had some terrific mentors, both male and female, who were Caucasian, it was hard to go through this process rarely being taught by or working with someone who looked like me.

Research—Applying Mathematics to Understand Vision

I study mathematical physiology, specifically looking at components in the visual system that lead to blindness. I collaborate with experimentalists and together we try to understand what causes blindness in diseases where the photoreceptors degenerate, such as in Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP). I have focused much of my attention on the photoreceptors in the retina, the rods and cones, together with the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) that works with rods and cones to facilitate vision.

I am the first person to dive into this area from a mathematical perspective. My research and publications on the subject provided the first set of mechanistic models and mathematical equations describing photoreceptor degeneration. I have 28+ publications with 12+ of them pioneering modeling of retinal processes. We developed a series of spatially averaged nonlinear ordinary differential equations models to investigate both the healthy and diseased retinas at the cellular and molecular levels. In my earliest publication in the area, we predicted the existence of something experimentally discovered a year later—the rod-derived cone viability factor (RdCVF) and proposed equations describing the dynamics of rod and cone outer segment (OS) number, and RPE cell number. We extended this model in another publication to account for mutated (phenotype) rods, which were used to describe the diseased state of RP. In another publication, the RP model was further extended to include a control input that represented RdCVF treatment, which was designed using optimal control. The metabolic contribution in RP to photoreceptor death was quantified in collaboration with an experimentalist through a mathematical model. With another experimentalist (the discoverer of RdCVF, Dr. Thierry Léveillard), we showed the role of RdCVF in RP coexistence and mathematically analyzed it.

My recent work extends to multi-scale predictive models that investigate cellular and molecular level dynamics contributing to degenerative process or diseases including Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD). I want my research to make a difference. Being sought out by some of the top experimentalists in the world for collaboration on how to stop photoreceptor degeneration (and mitigate blindness) has been a huge recognition from my point of view. It was incredibly rewarding when my collaborator Dr. Léveillard said it was because of our models and my discussion with him about their predictions that his team was able to identify previously unknown metabolic pathways that are now under investigation.

Mentoring and Perseverance

I see so many things in academia and outside of it that need to change to make an equal playing field, yet it seems that most people in positions of power are not willing to risk it to make a change. I feel like there are “fights’’ at nearly every step that would lead in the right direction.

Mentoring Roberto Alvarez, Danielle Brager, and students at ASU in 2019.

I am currently in my reflection stage and not sure how to best change academia and the world while not giving up all of me, especially given that there is no guarantee that what I do might make any noticeable difference. It’s tough. What often keeps me going are the many, very personal, and sincere messages I receive from former mentees of how I made a difference in their trajectory. The most touching ones are when they have told me that only after being away for a few years did they really appreciate the mentoring I gave them. Many will ask what they can do to become a mentor like me because they have not found people like me. I explain that I just do what I learned from my mentors who really truly cared about me—those who did not mentor me because they were trying to build an empire or check a box. I have fought many battles for my mentees when they were experiencing bias or unfair treatment by jumping in and changing the situation for them before they were completely broken. I have also fought for many who are not my mentees but who don’t have a voice or seat at the decision table or who are invisible and forgotten, often by making structural changes and creating opportunities. I sacrificed many things to give my mentees and many others equal access and opportunites. I try to do whatever I can to help my mentees realize their full potential and their dreams, in addition to listening and giving advice that I think is best for them irrespective of me. Each one of their successes gives me the motivation to continue. Each one of the mentoring awards I have won is also a validation that what I do actually makes a difference.

Receiving the American Association for the Advancement of Science Mentor Award in 2019.

A lot of mentoring is first learning about the individual because so many factors influence who we are today and why we make certain choices. Then it is a time-intensive endeavor to meet them where they are and to bring them up to their full potential.

As a postdoc, I co-wrote a grant to the National Security Agency (NSA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) to start my own REU. This led to the launch of the Applied Mathematical Sciences Summer Institute (AMSSI) the summer after my first year in my tenure-track job at Loyola Marymount Univeristy (LMU). The program was joint with Cal Poly Pomona and we split the time between the two universities, moving the students halfway through the program. Over its three years, we had 48 students, and five Teaching Assistants (TAs) participate in the program. All were either from underrepresented backgrounds or schools where research opportunities didn’t exist or were not available to them. Nearly one-third earned their PhDs, with many others earning their master’s. It was a very rewarding program and only stopped because I moved from LMU to Arizona State University (ASU).

As a postdoc, I co-wrote a grant to the National Security Agency (NSA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) to start my own REU. This led to the launch of the Applied Mathematical Sciences Summer Institute (AMSSI) the summer after my first year in my tenure-track job at Loyola Marymount Univeristy (LMU). The program was joint with Cal Poly Pomona and we split the time between the two universities, moving the students halfway through the program. Over its three years, we had 48 students, and five Teaching Assistants (TAs) participate in the program. All were either from underrepresented backgrounds or schools where research opportunities didn’t exist or were not available to them. Nearly one-third earned their PhDs, with many others earning their master’s. It was a very rewarding program and only stopped because I moved from LMU to Arizona State University (ASU).

I have given motivational talks to groups ranging from elementary school through high school students in addition to college students, professors, and high-level administrators. Each of these talks can get emotional as I’m giving examples from my life to drive home the message. One of the most emotional keynote addresses I gave was in 2009 to the recipients of the Presidential Awards for Excellence in Science Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring (PAESMEM). It was very special to be able to thank each of them on behalf of all their mentees and tell them how their efforts are appreciated even if not all the mentees come back and say thank you. It’s also important to keep in mind that great mentors are not just the ones that have won the big awards, but most important the ones who open the doors for others by creating opportunities and fighting the tough battles to bring about change.

Diversity and Inclusion in Mathematics

I am an applied mathematician and thus I usually see everything as a problem to be solved. I really have come to appreciate what is now known as “team science’’ where multiple people come together from their varied perspectives to try to solve a previously unsolved problem. I think the most challenging problems require this approach.

We need a society that is knowledgeable about STEM or at least appreciative of it! Since math describes and underlies nearly every aspect of STEM, every issue can be helped with the presence of mathematicians. Moreover, we really need to focus on team science where multiple approaches, even beyond STEM, are used to solve the most pressing problems of today.

In higher education, we talk about changing things for marginalized communities, yet we forget to include stakeholders from these communities (we bring high-level administrators or researchers to the table as “representatives’’ who are employed in institutions serving these communities but who have not been raised in these communities or have not lived through the experiences of those they represent).

The mathematics students and faculty need to reflect the U.S. population. I think one of the main barriers is a lack of understanding from the professors about what it means to be a professor. We judge people by their publications and not the impact of all their efforts (scholarly and otherwise). If we want to change academia and agree that we need all professors to be good mentors and to understand the diverse population they are working with, why should people object to requiring a Diversity/Inclusivity Statement and a Mentoring Statement in job applications and promotion documents?

From a different angle, individuals rarely solve the challenging problems of today. If we let those perpetuating the status quo also determine the research agenda, very little will change. We need to bring the richness of multiple backgrounds, including Latinx people, to be at the table and set the research agenda, yet it’s understandably hard for many of those in charge to step aside and let different perspectives weigh in.

In terms of societal/institutional structures, it’s the narrow-mindedness, micro-aggressions, and institutional racism that are the biggest obstacles to learning.

It will take many selfless and courageous people of every race, color, and way of life to eliminate these structures because there are too many vocal people (even if they are in the minority) that want to preserve the status quo or go back to how things used to be and there are too many people who don’t think it’s their problem and will stay silent. We have a generation of Latinx PhD mathematicians that wasn’t present when I started my journey and that really gives me hope that change is on its way. Some are oblivious to the Latinx situation but most are actively doing things to promote our community. Many majority mathematicians show us support too.

We need more Latinxs involved in math because of the need to approach challenging problems from different perspectives and to actually shift the focus of what problems we should be working on.

Advice

It’s great to want to change the world. But don’t lose yourself as you try to do it. There will always be detractors and haters, but ignore them as much as possible. Don’t doubt yourself and don’t let others define who you are or your path. Judge people by their actions and not just their words. Finally, while it’s great to have a mentor that looks like you, don’t think that this is a requirement. Some of your very best and long-term mentors may be Caucasian males, and one that may do the most damage to you personally and professionally might be a Latino.

Many times I am speaking to students who have had a rough path yet they have what it takes to overcome the adversity they have experienced. I had, and still have, a rough journey many times. Sometimes they just need to realize that people have done it before, are still struggling to make it in their respective career levels, and they are not alone. The path won’t often be easy, but the rewards, in the end, are worth it.

I have had some terrific and some very hurtful and toxic mentors who are mathematicians. But I have also had great mentors that are not in math and some are not even in STEM, but they are very perceptive, understand things, and can give relevant advice. It’s them needing to realize who I am as a person and what may be best for me. Many people from all walks of life will share and support your goals and dreams. Perhaps there is a correlation between those supporters and people with your characteristics, but by no means should you limit your mentors and advocates to just those with certain characteristics (such as being Latinx). At the same time, believe someone the first time they show you their true colors.

Previous Testimonios: