Guest Post by Corrine Yap

Uniform Convergence is a one-woman play, written and performed by mathematics graduate student Corrine Yap. It juxtaposes the stories of two women trying to find their place in a white-male-dominated academic world. The first is of historical Russian mathematician Sofia Kovalevskaya, who was lauded as a pioneer for women in science but only after years of struggle for recognition. Her life’s journey is told through music and movement, in both Russian and English. The second is of a fictional Asian-American woman, known only as “Professor,” trying to cope with the prejudice she faces in the present. As she teaches an introductory real analysis class, she uses mathematical concepts to draw parallels to the race and gender conflicts she encounters in society today.

– synopsis that was included in the MAA MathFest 2018 program

In 2016, at a graduate school open house, I was told by a math professor that I would fit right in because they had “a large group of international students from China.” I responded, “Oh, I’m not international; I’m from Missouri.” He replied, “Well, yes, but it would be a good group for you.” Throughout my life, I’ve had many little exchanges like this. Uniform Convergence was not born out of these experiences but rather out of my struggle to discuss these experiences (and race in general) with other people.

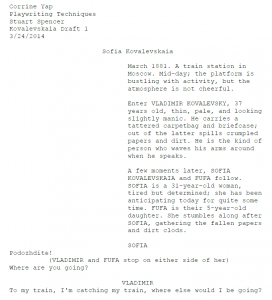

Kovalevskaya Draft 1: 3/24/2014

Uniform Convergence began as an end-of-term project in my first playwriting class. The assignment was to write a history play: something about a historical person or event. As a math and theater “double major” at Sarah Lawrence College (we didn’t actually have majors), I jumped at the chance to be interdisciplinary. I had initially chosen Sophie Germain, but my analysis professor/mentor suggested Kovalevskaya. “Her life was full of drama. And Sophie Germain has already been done.” My professor wasn’t wrong.

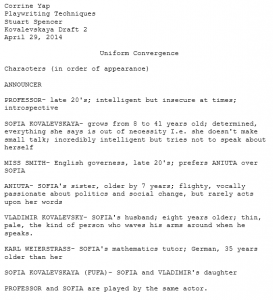

Kovalevskaya Draft 2: 4/29/2014

At the same time, certain news stories began cropping up: stories of students of color calling out college administrators for their lack of progress in catering to a non-white student demographic. Yale, Oberlin, Claremont McKenna, and eventually Sarah Lawrence, to name a few. In the years that followed, incidents of hate and intolerance seemed to be on the rise.

In response, I wrote. Not for anyone but myself, at first. I wrote monologues given by characters who were facsimiles of myself on stage, ranting about injustice and emotions and the lack of diversity in my theater department’s play choices and casting choices (this was a source of heated debate and discussion until the end of my time at Sarah Lawrence, and probably still is).

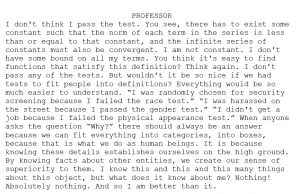

I was frustrated. I was also taking real analysis. So I wrote a monologue for a professor who was teaching analysis but who was also angry and tired and fed up. I put it in my Sofia play, between a scene of her with Karl Weierstrass and an argument at the train station between her and her husband before they part for the last time. I didn’t know what this professor had to do with Sofia, but I knew that they shared a feeling of powerlessness in a world that was not built for them. I didn’t want my history play to live in the past. It had to give the audience something to take with them when the play was over. I presented this mish-mash of scenes in class, and the feedback was unanimous: this is going somewhere; keep working on it.

Uniform Convergence Draft 5.5: 12/11/2014

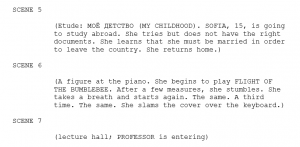

In the following year, I studied abroad – theater in Moscow and math in Budapest. Slowly the play morphed from a cast of 10 to a cast of 2; from pages and pages of dialogue between Sofia and her sister, Sofia and her husband, Sofia and Weierstrass, to “etudes”: wordless physical scenes that are the building blocks of much of Russian theater; from a jumble of monologues relating math and my personal life to the slow progression of a professor reacting to rising tensions on a college campus.

Its first performance was on April 27, 2016 at Sarah Lawrence College. At the time, it was a “solo show with two people”; a second actor played Sofia’s husband Vladimir. I think of this draft as the one with the most frills and the most self-indulgence. Because I had the resources of a school theater department known for being “experimental,” I could pull out all the stops: walls made of math papers taped together from floor to ceiling, a character called “Figure at the Piano” whose hands were live-feed projected onto the chalkboard, a semi-dance sequence to the song “Start Wearing Purple.” Looking back, I can see why the Professor character has remained mostly unchanged since Draft 7 while Sofia’s story looks almost nothing like it did before. From the beginning, the Professor has represented what I wanted to say, the things that I wanted the audience to know, and that hasn’t changed. But I had to figure out how to fit Sofia’s story into that.

Uniform Convergence Draft 12: 3/3/2016 |

Performance at Sarah Lawrence College, April 26, 2016 Pictured: Corrine Yap and Edunn Levy (playing the part of Vladimir Kovalevsky). Photo by Abigail Clark. |

After I started grad school at Rutgers University (I had decided that it would be easier to have a career in math and do theater on the side than to have a career in theater and do math on the side), the play was accepted to the NuWorks Festival at the Pan-Asian Repertory Theater in NYC. This time, I performed on my own – no director, no second actor, no designers. There were no chalkboards available in the space, so I taped sheets of butcher paper to the walls and danced with a coat rack that played the part of Vladimir.

Uniform Convergence Draft 12: 3/3/2016

Again, you can see why I continued to edit the Sofia storyline.

Uniform Convergence Draft 14.5: 3/6/2017

This brief off-Broadway run brought two questions to my mind: (1) What is the purpose of this play? and (2) Who is this play for?

I thought I had always known the answer to (1): the point is to share my experiences with prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination, as a woman and an Asian American in a STEM field. It has taken a while, but I have finally accepted that my story is one worth telling. A worry that I (and I think a lot of other artists) have is about self-indulgence: why should my story matter? Who cares? Offering up something so personal for public viewing always raises these questions for me. Even writing this blog post, I am asking these questions of myself. Over time, I’ve had enough people come up to me and thank me, or tell me a personal story, or ask me to perform at their school that I don’t agonize over the play’s existence anymore. But what is the message of the play? I don’t know that there is one. My hope is that the play starts a conversation, or makes people think about issues that they might not have considered before.

Uniform Convergence Draft 15: 5/3/2017

This answer to (1) doesn’t address approximately half of the play: why Sofia? NuWorks made it clear to me that Sofia’s presence in that version of the play was more of a hindrance, an extraneous plotline, than a necessity. I wanted the play to be about Sofia’s struggle just as much as it detailed my own. In Drafts 1 through 15, however, Sofia’s story was centered around her conflict with her husband. This was supposed to be a play about two women fighting for a place in a male-dominated field, and here I was making half of the play rely on a male character! So that summer, I killed my favorite scene – the first scene I had written, a scene at a train station where Sofia leaves Vladimir for good, the scene that I had continued to include in every draft only because everyone in my playwriting class said it was their favorite scene. I killed the coat rack and rewrote Sofia’s story to be about her. This was Draft 16.

Uniform Convergence Draft 16: 10/22/2017

That brings me to question (2): who is this for? Before NuWorks, I didn’t think it was for math people. I was worried that my classmates and professors in grad school would think I was weird for having a one-woman show, or feel uncomfortable with the subject matter. Regarding the former, I was flat-out wrong. Each of my performances in the past year has resulted from someone seeing a previous performance and asking, “Can you come to my school?” Even my most recent show at the MAA MathFest was a result of Pat Devlin (former Rutgers grad student, now postdoc at Yale and probably Uniform Convergence’s greatest champion – he has seen the show four times) pointing me in the right direction.

Regarding the latter, I’ve come to realize that the discomfort of dealing with subjects like race cannot and should not be avoided. Conversations about stereotyping and diversity and inclusion need to happen. As I mentioned, this play resulted from my struggle to have such conversations: it’s easy to talk to people who agree with me but hard to bring up such topics with people who don’t – or worse, people whose opinions I don’t know. If I tell them that story about the professor who believed I have more in common with Chinese-born-and-raised students than with fellow Americans, will their response be “Wow, that’s awful!” or “Well, he’s got a point…”? I’m horrible with confrontation, and I was scared of receiving a response I wasn’t prepared for.

Regarding the latter, I’ve come to realize that the discomfort of dealing with subjects like race cannot and should not be avoided. Conversations about stereotyping and diversity and inclusion need to happen. As I mentioned, this play resulted from my struggle to have such conversations: it’s easy to talk to people who agree with me but hard to bring up such topics with people who don’t – or worse, people whose opinions I don’t know. If I tell them that story about the professor who believed I have more in common with Chinese-born-and-raised students than with fellow Americans, will their response be “Wow, that’s awful!” or “Well, he’s got a point…”? I’m horrible with confrontation, and I was scared of receiving a response I wasn’t prepared for.

So Uniform Convergence became my conversation-starter, my jumping-off point, my way of telling people, “Here’s what I want us to be talking about.” I found allies in my classmates and colleagues with whom I had chatted about tensor products and graph embeddings but never dared to broach the topics of politics or race. I still don’t dare, sometimes. But I am using this post to challenge you – and thereby hold myself accountable – to have these conversations, to talk about these things that we “aren’t supposed to talk about” in math.

Ask a colleague if they knew that in 2015, women made up almost 1/3 of math doctoral recipients but only 22% of doctoral hires.[1] Ask if they have any female undergraduate students. Ask if they’ve asked any of those female students about attending graduate school. Ask if they know that the number of non-white Americans who earn math Ph.D’s each year has remained at 6 to 7.5% of all math Ph.D.’s granted that year in the U.S., for the past 15 years.[2] And yes, that includes Asian Americans. Ask if they know the names of their students. Now ask if they know the names of their east Asian international students. Now ask if they know which Asian students are not international students. (Perhaps they will say none, to which you may respond “Are you sure?”) Ask if they care about representation of women and minorities in mathematics. Ask what they think they can do to effect change. Perhaps they will say nothing. Perhaps it’s because they’re a graduate student with a million things to do and no real power. Perhaps it’s because they’re just a small part of a large and largely unjust system, and it’s hard to figure out what to do, what to say, how to say what to which people to make it matter. That’s okay. You had a conversation about it, and that’s already a step forward.

Corrine Yap is a math Ph.D student at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ. For photos, videos, and reviews of the show, visit www.corrineyap.com/uniformconvergence. If you’d like to invite Corrine for a performance, please send her a message at www.corrineyap.com/contact.

[1] according to the AMS Annual Survey http://www.ams.org/profession/data/annual-survey/demographics

[2] Ibid.

Well done! Thank you.