Guest post by Dr. Mike Egan of Augustana College.

Here

“If the streets shackled my right leg, the schools shackled my left. Fail to comprehend the streets and you gave up your body now. But fail to comprehend the schools and you gave up your body later. I suffered at the hands of both, but I resent the schools more.”

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ deservedly acclaimed Between the World and Me provides an honest and jarring window into his experience as a Black man in present-day America. His portrayal of his time in the K-12 school system is particularly unsettling: he describes monotonous rote instruction, a not-so-implicit curriculum that esteems conformity over creativity, civics lessons preaching social passivity over political action, and worse. “I came to see the streets and schools as arms of the same beast,” he writes. “[F]ear and violence were the weaponry of both.”

These messages can readily be taken as an affront to members of the predominantly white American teaching force that serve a majority non-white population of students. Speaking for myself as one member of this force, I must acknowledge a feeling of defensiveness come on as far as Coates’ words might be applied to my own practice. I accept my imperfections as a teacher, but surely I’m no agent of fear and violence, right? My defensive impulse subsides when I recognize that Coates is not pointing directly at my classroom, but rather at a collective system that effectively serves to maintain the privileges of some while limiting or outright damaging the humanity of others. I have come to take ownership of the painful and unfortunate fact that, as a (White) teacher in this system, I am a contributor to its unjust totality. I suspect that White readers of this blog have arrived at similar conclusions, and perhaps share my view that we must develop a critical mass of justice-minded White folks who will acknowledge the dehumanizing effects of institutional racism and collectively work at the side of all who seek justice to dismantle a system built on White privilege.

These messages can readily be taken as an affront to members of the predominantly white American teaching force that serve a majority non-white population of students. Speaking for myself as one member of this force, I must acknowledge a feeling of defensiveness come on as far as Coates’ words might be applied to my own practice. I accept my imperfections as a teacher, but surely I’m no agent of fear and violence, right? My defensive impulse subsides when I recognize that Coates is not pointing directly at my classroom, but rather at a collective system that effectively serves to maintain the privileges of some while limiting or outright damaging the humanity of others. I have come to take ownership of the painful and unfortunate fact that, as a (White) teacher in this system, I am a contributor to its unjust totality. I suspect that White readers of this blog have arrived at similar conclusions, and perhaps share my view that we must develop a critical mass of justice-minded White folks who will acknowledge the dehumanizing effects of institutional racism and collectively work at the side of all who seek justice to dismantle a system built on White privilege.

[Jump to sections: Here, There, Back Again, or the Epilogue about critique and design]

Of course, we are far short of such a critical mass. From my vantage point as a (mathematics) teacher educator, I worry that the current generation of White pre-service teachers is no more concerned about institutional racism than their forebears. I have encountered too many undergraduates that seem unable or unwilling to work past the individualistic defensive posture that I described in my own self earlier. If the subject of race is broached, template responses range from “I am not a part of this problem” (more specifically, “I treat everyone with respect regardless of race or ethnicity. I am not a racist, so I will not contribute to a racist system.”) to the more insidious, “Racism is no longer a problem in America…people of color play the race card to gain advantage, and I tire of hearing their overblown or outright false complaints.” Coates himself is fully aware of how readily his arguments about the state of America can and will be dismissed. In Between the World and Me, written as an open letter to his son, he writes, “I [can] not save you from the unbridgeable distance between you and your future peers and colleagues, who might try to convince you that everything I know, all the things I’m sharing with you here, are an illusion, or a fact of a distant past that need not be discussed.”

I agree that Coates’ contention that American schools are a central component of a White supremacist society is no illusion, but I cling to the belief that the gaps between those who see this and those who don’t are not unbridgeable. White people must contribute substantially to the construction of these bridges, though.  As Chayla Haynes and Nicole Joseph point out in their introductory chapter of Interrogating Whiteness and Relinquishing Power, one way to begin the process of this bridge-building is to develop racial consciousness in White teachers. Drawing from Haynes’ earlier work, racial consciousness is defined as “an in-depth understanding of the racialized nature of our world, requiring critical reflection on how assumptions, privilege, and biases about race contribute to one’s worldview” (Haynes, 2013, quoted in Joseph, N.M., Haynes, C., & Cobb, F., 2016). But how can teacher educators help pre-service teachers develop racial consciousness when so many White undergraduates seem to have a stubborn impulse to reject or dismiss suggestions that race continues to be a central problem in American schools?

As Chayla Haynes and Nicole Joseph point out in their introductory chapter of Interrogating Whiteness and Relinquishing Power, one way to begin the process of this bridge-building is to develop racial consciousness in White teachers. Drawing from Haynes’ earlier work, racial consciousness is defined as “an in-depth understanding of the racialized nature of our world, requiring critical reflection on how assumptions, privilege, and biases about race contribute to one’s worldview” (Haynes, 2013, quoted in Joseph, N.M., Haynes, C., & Cobb, F., 2016). But how can teacher educators help pre-service teachers develop racial consciousness when so many White undergraduates seem to have a stubborn impulse to reject or dismiss suggestions that race continues to be a central problem in American schools?

For the past five years colleagues and I have approached this challenge by prompting students to examine institutional racism in a foreign setting, and then to uncover parallels between racist practices abroad and racist practices in the U.S. This happens via a school-based, study away experience we have fostered for our institution’s pre-service teachers in Jamaica. This optional (and, obviously, appealing-to-students) program is supplemental to the formal teacher education program, hence it enables instructors to approach teacher education in ways that are completely unencumbered by the mandates and directives of the U.S. system (that is, the Jamaica program is not accountable to the state teacher education standards, we are not pressured to prepare our students for high stakes external assessments such as the edTPA, etc.). In short, since this program operates outside the U.S. teacher education system, it opens up ample space for instructors to critique the system and offer teaching candidates alternative ways of viewing the role of schools in

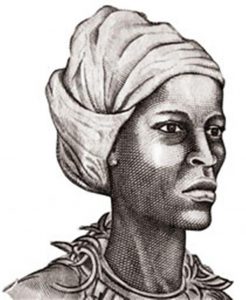

Jamaica’s National Heroine, Nanny of the Maroons

society, and also to deeply question what it means to teach and learn. In terms of developing pre-service teachers’ racial consciousness, the overseas setting of the program deflects that “White defensiveness” instinct described earlier. That is, since the experience begins by focusing on the Jamaican context, White American teachers begin their exploration of race and colonialism and oppression from a distance. We examine the violent history of Jamaica (Spanish colonization, enslavement and rape of the native Taino people, importation of African slaves as the Taino population depleted, British overthrow of Spanish control but maintenance of their slavery institution, ongoing struggles during 55 of years of tenuous “independence” from past colonizers and present neo-colonizers). Students in the program are appalled by these injustices, and they applaud the actions of past and present resistors (Nanny, Cudjoe, Sam Sharpe, Paul Bogle, Marcus Garvey, modern reggae musicians and social commentators). The program culminates with a 2-week trip to the island and a 1-week teaching placement in a Kingston school. As will be elaborated later, the school-based experience is usually cited as the most impactful component of the course. The American teachers form human relationships with young students from Kingston’s inner city, hence making the issues we read about in the preceding academic term feel more personal and real. The program does not end when we leave the island, though. Return programming (as well as course material addressed prior to departure) prompts students to explore parallels between the situation in Jamaica and the situation in the U.S. (such as the Black experience in Jamaica and the Black experience in the United States, between European ((Spanish and British)) colonization of Jamaica and U.S. colonization of its own native peoples and their lands, between the brave resistors of the ongoing Jamaican struggle and the brave resistors of the ongoing American civil rights struggle, between the official curriculum of Jamaican schools and the official curriculum of American schools, etc.). [Editor: For a non-US perspective on the themes in this paragraph and post, see the comments below coming soon.]

Developing racial consciousness is a lifelong process, so I make no claims that students fully “get it” after this course (nor do they all arrive in the course as blank slates completely devoid of racial consciousness). I acknowledge that I don’t fully “get it” myself, but I do know that my time as a high school math teacher in Jamaica from 1995-2003 pushed me to become sharply aware of the role of race in societal power and privilege. I have also seen evidence that the Jamaica Program I now co-direct spurs some degree of development in many of the participating pre-service teachers. As such, I believe that this sort of program represents one promising method that teacher educators might use in the uphill battle of pushing the racially privileged of American society to acknowledge their privilege and then play a part in dismantling it for the sake of justice for all. The next section of this essay will elaborate on some of the big ideas we explore in the undergraduate course that is associated with our Jamaica program, thus giving readers a stronger sense of how an examination of “there” (the Jamaican context) can help White future teachers begin to encounter vital issues of race and oppression that are very pertinent “here” (in the U.S. context where these teachers will spend their careers). This will be followed with some reflections provided by White math teachers who participated in the Jamaica program and indications about how the experience impacted their own teaching practice. [Editor: Egan also discusses making sure the program is beneficial in the eyes of the Jamaican hosts in the Epilogue.]

There

They say what we know is just what they teach us,

And we’re so ignorant ‘cause every time they can reach us…

Well, what we know is not what they tell us

We’re not ignorant, I mean it; and they just cannot touch us.

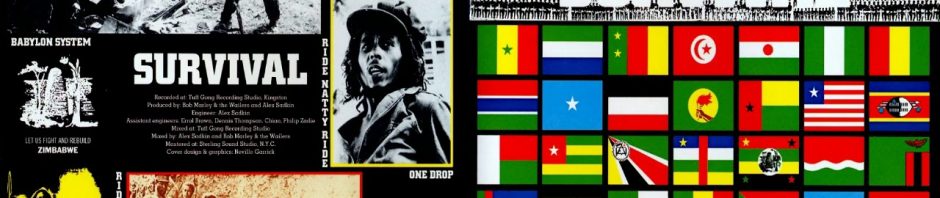

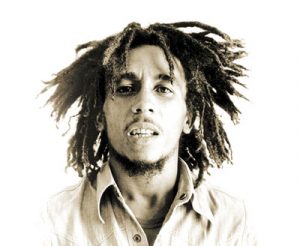

-Bob Marley and the Wailers, “Ambush in the Night”

The title of the pre-trip course is “Songs of Freedom: Music, Education, and Politics in Jamaica.” The course is ambitiously designed to expose students to aspects of Jamaican history and culture that might prepare them to engage the people in a more informed and respectful manner, and also to provide some exposure to the formal Jamaican education system so that our college students are more prepared to serve in the program’s three partnering schools. We recognize that these goals are unattainable in the context of a college course, but we still feel it is necessary to make some progress toward these objectives. The course leans heavily on Jamaican-authored texts (including books, films, and extensive use of reggae lyrics) as we strive to understand “insiders’ perspectives” as much as possible.

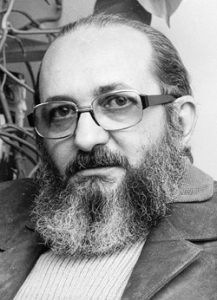

We do use one secondary source that is intended to help us frame the implications of formal education in a post-colonial society: Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Readers familiar with this book will know that it is a dense philosophical text, and might wonder if it would be accessible to undergraduates. We have found that reggae music generally and Bob Marley lyrics specifically can be very helpful in the work of understanding and appreciating Freire’s message. The above lyrics from “Ambush in the Night,” for example, help illustrate Freire’s concepts of “banking education” (an oppressive approach to teaching through which teaching is viewed as an act of “depositing” knowledge into the minds of presumably ignorant students, and those in power decide which knowledge is worth depositing) as well as his method for a liberating education (one in which the existing knowledge and everyday reality of the people is used as a starting point in the educational process, learners begin to develop consciousness of the forces that oppress

them, and then engage in a political process of transforming their present reality into a more just world).

Freire demonstrates that widespread, systemic use of the banking approach to education is a powerful (and violent) tool for maintaining a status quo that privileges those in power while keeping oppressed groups in a place of subjugation. Again, Marley echoes Freire’s arguments with simpler yet equally potent language. His song “Crazy Baldheads” exposes the oppressive potential of formal education, and offers a haunting reference to its cousin, the prison-industrial complex:

We build your penitentiaries, we build your schools

Brainwash education to make us the fools

-Bob Marley and the Wailers, “Crazy Baldheads”

Freire and Marley shoot holes in the individualistic, conventional wisdom that formal education leads to social and economic mobility for members of lower classes. Freire contends that the oppressor class is interested only in maintaining its power, and that its educational institutions are tools of social reproduction. Marley concurs, declaring in his song “Babylon System” that “you can’t educate I for no equal opportunity.”

Echoes of Freire’s critical educational ideas are not confined to th e books and songs of the 1970s, though. In our class we engage many other texts that convey the troubling message that society’s systems (including the education system) are stacked against poor Jamaicans. This is a clear theme in Nicole Dennis-Benn’s 2016 novel Here Comes the Sun and in multiple reggae songs spanning the decades. Vybz Kartel’s 2010 dancehall track, “Something Ah Go Happen,” expresses this in the Patois:

e books and songs of the 1970s, though. In our class we engage many other texts that convey the troubling message that society’s systems (including the education system) are stacked against poor Jamaicans. This is a clear theme in Nicole Dennis-Benn’s 2016 novel Here Comes the Sun and in multiple reggae songs spanning the decades. Vybz Kartel’s 2010 dancehall track, “Something Ah Go Happen,” expresses this in the Patois:

Youth leff school, from the school to the corner

Qualified, but just true him area

Dem say him nuh fit the criteria

-Vybz Kartel, “Something Ah Go Happen”

That is, a young person from a poor community works hard in school and graduates. Though he now has the academic qualification to get a decent job, it doesn’t matter. His inner city street address is a scarlet letter that prevents employers from hiring him.

Marley, Dennis-Benn, and Kartel all suggest that, for poor Jamaicans, school is useless at best and oppressive at worst. This is hardly a message that would get future teachers excited about teaching in inner city Kingston schools. I will soon elaborate on why these critical texts are chosen for the class, but will first point out that the critical perspectives are not the only Jamaican perspectives about schools and schooling that are examined in class. Jamaicans as a whole hold utmost respect for the social mission of education. Teachers are held in much higher esteem in Jamaican society than they are in U.S. society (though it is hard to imagine any society on the globe having less respect for its teachers than the U.S.). Many texts we examine convey the fundamental Jamaican story that education is important and worth struggling for (songs such as Buju Banton’s “Untold Stories” and Sizzla’s “Thank You Mama” tell this story in touching ways). So, while we wrestle with the idea that formal education has potential to be a tool of violence and oppression, we also see that Jamaicans continue to find hope in education and that we, as short-term visitors volunteering in schools, have an opportunity to contribute something (miniscule, but still something) to that enterprise.

The critical perspectives of Freire, Marley, Dennis-Benn, Kartel and others are vital, though, and our American students see plenty of evidence in their study of Jamaican history to recognize that these critics are on to something. How can a small (“White”) minority keep a large (“non-White”) majority in the chains of slavery for multiple centuries if they don’t have systemic tools to prevent rebellion? Why does skin color continue to correlate strongly with wealth on the island to this day if the vast majority of the country’s citizens have the pigment associated with poverty? Again, clearly there must be a system in place that maintains these socioeconomic hierarchies. White American outsiders can be quicker to see this in the history and literature and art of a foreign land than they are to see the mechanics of an analogous system in their own country.

Seeing a system of oppression in a foreign land is still seeing a system of oppression, though. Something that may have been invisible once can now be seen, and now that it has been seen, one is more capable of recognizing it elsewhere. Maybe even in one’s own backyard.

Back Again

How can you be sitting there telling me that you care?

When every time I look around the people suffer in their suffering

In every way and everywhere

-Bob Marley and the Wailers, “Survival”

I launched this essay with a jarring quote from Ta-Nahesi Coates: a quote, I feel, that leads White folks to an uncomfortable crossroads. Will we reject Coates’ claims that schools can be (and very often are) institutions of violence and oppression, or will we accept that Coates is on to something and hence recognize that we have a moral obligation to join a struggle aimed at making our society (and schools) more just? My contention is that the latter approach is on the side of justice, while the former is a sign of White privilege and racism.

The lyrics launching this section of the essay provide an equally painful punch to the White gut, but one I feel the students in the Jamaica program are prepared for by the end of the experience. Again, by the end of the Jamaican experience, I believe the students can clearly understand why Marley would express these sentiments in the context of Jamaican history generally and 1970s Jamaica specifically. But these lyrics from “Survival” are uncomfortably expressed in the present tense, have an uncomfortable universal tone, and reasonably point us toward people like Coates who express a suffering felt by Black folks (and others) in the present-time, proximal setting of the United States. If we like to think of ourselves as people who care (and teachers usually do), then how can we ignore the suffering that happens everywhere? Who are we to reject the uncomfortable claims of Coates, Kaepernick, Black Lives Matter, and all canaries desperately chirping in the mine that are warning us of dangerous conditions that will dehumanize and destroy us all if we don’t work together toward justice?

For this reason, this song is a helpful bridge leading our group back again from our study and immersion in Jamaica toward our lives as American citizens (and usually school teachers) moving forward. Students are required to reflect on their Jamaica-based learning and articulate how insights drawn from the experience can be applied in their lives moving forward. It is hoped (and often somewhat realized) that students will have developed their racial consciousness as a result of the experience and recognize the many parallels between the ongoing struggles of Jamaicans and the ongoing struggles of minority groups in the U.S. A quick review of the previous section of this essay will show that parallels shouldn’t be hard to find. Freire and Marley point out the oppressive nature of “banking” education; what does this imply about America’s increasing reliance on standardized tests? They also shed light on the education system as a powerful tool of social reproduction; how do we as (caring?) Americans rationalize or resist our own system where the neighborhood where a child is born predicts the quality of schooling and economic opportunities they will receive? Vybz Kartel laments that poor Jamaican youth cannot gain employment even after they have graduated from school; how can we as Americans tolerate a society where our Black men must earn more educational credentials than their White peers in order to land the same jobs?

For this reason, this song is a helpful bridge leading our group back again from our study and immersion in Jamaica toward our lives as American citizens (and usually school teachers) moving forward. Students are required to reflect on their Jamaica-based learning and articulate how insights drawn from the experience can be applied in their lives moving forward. It is hoped (and often somewhat realized) that students will have developed their racial consciousness as a result of the experience and recognize the many parallels between the ongoing struggles of Jamaicans and the ongoing struggles of minority groups in the U.S. A quick review of the previous section of this essay will show that parallels shouldn’t be hard to find. Freire and Marley point out the oppressive nature of “banking” education; what does this imply about America’s increasing reliance on standardized tests? They also shed light on the education system as a powerful tool of social reproduction; how do we as (caring?) Americans rationalize or resist our own system where the neighborhood where a child is born predicts the quality of schooling and economic opportunities they will receive? Vybz Kartel laments that poor Jamaican youth cannot gain employment even after they have graduated from school; how can we as Americans tolerate a society where our Black men must earn more educational credentials than their White peers in order to land the same jobs?

I’ve outlined here the potential that our Jamaica Program has for developing future teachers’ racial consciousness. I’m an experienced enough teacher to know that my visions for what the students might learn (or should learn) is very unlikely to match with what the students actually internalize as they move on with their lives. I seriously doubt that any student that passed through this experience connected all the dots in the way I have done in this essay, and why should they? I’ve been thinking about this stuff for 22 years, while they haven’t even lived for 22 years as they experience the course. Still, I’ve already claimed that I’ve seen evidence that many students do construct a more nuanced racial consciousness as a result of this experience, and I will close this essay by sharing some of that evidence.

Given that this post appears on a blog of the American Mathematical Society, I will focus on the mathematics teachers that participated in our Jamaica Program (the Program is not confined to future math teachers…most participants are not future math teachers). Furthermore, since I have expressed an ambitious goal for the program of developing lasting and applicable racial consciousness in teachers, I felt it would be interesting to consult alumni of the program that are presently working as math teachers. I reached out to our math-teaching alums and asked them (in a very open-ended manner) to share reflections on how the experience impacted them as teachers, and, more specifically, if it impacted their approach to working with students from diverse racial groups. A thematic summary of the responses I received are shared below. While the number of respondents is low (5 of 12 alums responded to the single email I sent out to the email addresses I had), the responses are encouraging. Again, these alums were able to articulate a lasting impact that the Jamaica Program had on them as they entered the profession. Furthermore, these are voluntary, open-ended responses (as opposed to lines drawn from current students’ required end-of-term papers where they might feel pressured to pen professor-pleasing prose).

In his contribution to the 2016 volume Interrogating Whiteness and Relinquishing Power, Frederick Erickson argues that direct experience of working with people of color is a powerful way of developing justice-oriented racial consciousness among White professionals. Direct experience can disrupt dominant (racist) narratives that portray students of color as unmotivated or anti-intellectual. Working alongside students of color promises to “counter negative stereotypes” and provide “‘existence proofs’ [showing] that something else is possible than the overgeneralized ‘figured view’ of those who are ‘othered’” (p. 77). Erickson’s observations certainly resonate with our program, as almost all of my respondents commented on how they were struck by the Jamaican students’ respectful demeanor and devoted academic work ethic. Indeed, a common sentiment was the White American teachers’ perspective that the Black Jamaican students they taught had a stronger work ethic than what they have encountered as students and teachers in American classrooms. Respondent Jessica observed, “The students had an inherent desire to learn, and education was valued instead of being seen as a requirement, as is often the case in America…I didn’t need to [establish myself as a disciplinarian] in order to earn their respect; they gave it willingly.” Respondent Brandon added further, “the students were very respectful. The room was far too hot and far too full in my opinion, but these students wanted to learn. They were more respectful than the high school students I went to high school with.” The experience-based perspective that Jessica and Brandon gained certainly contradicts commonly held stereotypes about Black, urban students. Quite contrary to the dominant assumption that Black students are undisciplined and unwilling to exert effort in school, Jessica found that her students approached the learning environment in a highly respectful way, while Brandon noted that the students maintained a high level of focus and care despite the challenging reality of being in an overcrowded and overheated classroom.

Respondents also articulated that the Jamaican experience forced them to think about how cultural differences within the classroom must be taken into account as teachers plan lessons and construct a learning environment. Respondent Tyler shared the following observation:

I grew up experiencing very little out of my cultural group (small town, middle class, white America). The Jamaica trip provided me an opportunity to get outside of that comfort zone I had grown up in. Simply the opportunity to work with students outside of my culture gave me experience that helped me learn more about students. We were made aware of our cultural differences in the Jamaica classes at Augie. I believe simply being aware of the differences helps us as teachers to better serve the students.

Tyler hints that the cultural differences he was directed to think about through our program continue to influence his teaching to this day. Jessica gets more specific, articulating details about how insights from the Jamaican experience transfer to her current teaching setting:

[T]eaching in Jamaica forced me to think about context before content. Who am I teaching? Where are they physically? Where are they mentally? How is this education going to alter the answers to those previous three questions? Because the students’ backgrounds were radically different from my own, I didn’t have a touchstone for reference, just as I didn’t when I began teaching at Milltown [a pseudonym for Jessica’s current teaching placement]. I learned to think quickly on my feet, and to gather evidence in answer to those questions without directly asking them. Because of this, I felt more confident teaching in Milltown, a school not only culturally different from my previous experience in size, but also a school with a cultural divide. According to 2016-17 data, 56.9% of students at Milltown High School are white, while 41.9% are Hispanic. The questions I began to develop while in Jamaica came into play with both ethnic groups as I transitioned, and learned the cultural norms both for the town itself and the subgroups of students.

Far from subscribing to the objectivist view that “math is math… it transcends culture,” the Jamaican experience helped these teachers recognize that they must be sensitive to cultural ways of knowing and communicating if optimal teaching and learning is to occur in the mathematics classroom. This is certainly one mark of a developed racial (and cultural) consciousness.

Earlier I argued that Ta-Nehisi Coates’ social commentary brings well-meaning White folks to a crossroads: will we reject the claim that racism remains a major social problem, or will we acknowledge that race-based privilege and oppression exists and that we must be prepared to join in a struggle aimed at dismantling oppressive systems? I have argued that the latter approach is the just approach, and I now serve as a teacher educator because my hope is that future teachers will join in that struggle. Of all my efforts, I sense that the Jamaica Program is among the most powerful methods I use that helps future teachers develop social consciousness. Respondent Keith provides a particularly interesting “existence proof” of this claim. Keith joined me in Jamaica during his junior year, and has been serving in Tanzania as a Peace Corps volunteer since his graduation in 2016. He writes, “I have grown so much as a person and I put most of the gratitude on the Jamaica program and never would have [joined the Peace Corps] without that experience.” Keith adds further comments that show he views his role as being one contributor to an ongoing and complex struggle for justice (and certainly not a “White savior”). Before he graduated, I shared an insight I have developed in my own ongoing work in the social realm: individuals really don’t make much of a difference in the face of societal injustices, but committing ourselves to collaborative work for justice is still the right thing to do. In his recent message to me he wrote

I didn’t really understand what you meant until I got here. You were definitely right about this and there have been all kinds of ups and downs. In Peace Corps we like to say “we won’t sit in the shade under the trees that we plant.” Perhaps we won’t see any changes made, but the seeds are planted and ideas are shared.

Keith’s comments reflect that he recognizes the long-term nature of social change, and the centrality of dialogue as a central component in this ongoing process.

The passages I’ve quoted from Coates’ Between the World and Me and Marley’s Survival haunt me, but the reflections I received from math teaching alumni of the Jamaica Program give me hope. Coates and Marley describe a cruel, dehumanizing society. It is haunting to reflect on the layers of complexity that construct the oppressive whole, and one can quite rationally feel powerless to change it. As individuals… possibly as individual White people particularly… we are effectively powerless. But, as Freire and others have noted, those of us with privilege can legitimately join in a larger struggle for justice. To do so, we must engage in a process of dialogue with those that suffer in society, learn about their reality, and work with them to transform that reality. Or, to quote Marley:

We Jah people can make it work

Come together, and make it work

-Bob Marley and the Wailers, “Work”

Epilogue: Design Considerations for Teacher Educators

In this post I have offered a pedagogical method for developing racial consciousness in pre-service teachers: examining institutional racism in a foreign setting first, and then prompting pre-service teachers to uncover parallels between the practice of racism abroad and the practice of racism in the U.S. While I hope that readers are persuaded that this method holds promise, I also recognize that readers might wonder if it is realistic to transfer aspects of this approach to their own institutions. Clearly an overseas program will have serious resource implications. Even if resources are available, the challenge of developing a meaningful and respectful partnership with a foreign institution is formidable. With this epilogue, I share reflections on how our program approached these challenges and offer suggestions for what other institutions should bear in mind if they choose to embark on a similar program.

1. Relationships first. To put a new spin on an old cliché, “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know.” If your goal is to establish a partnership with a school in another country, ensure that there is some form of meaningful and trustful relationship with school leaders first. Our Jamaica program had a fairly straightforward “in” as I served as a teacher at one of our partnering schools…a high school…for seven years. I was connected to the principal and several teachers. They were familiar with the contributions I made to the school years earlier, knew that I cared about the school and its mission, and therefore knew that I would ensure that my students’ engagement with their students would be respectful and mutually beneficial.

Certainly my existing relationship with a Jamaican high school was an asset that most other teacher education programs won’t have, but I am compelled to point out that human connections with overseas schools are likely available if you search for them. Consider reaching out to your institution’s international faculty, students, and/or alumni to see if they are interested in serving as an intermediary in launching a partnership with a school abroad.

A human connection can open the door to partnership, but be prepared to spend a substantial period of time nurturing the relationship with your overseas partner. Our Jamaica program actually partners with three different schools (a high school, an elementary school, and an alternative school). Again, I have a well-developed relationship with the high school, but our program’s engagement with the other two schools has gone through a slow but steady trust-building process over the past five years. All three partnering schools are Catholic schools administered by the Sisters of Mercy of Jamaica, so my connection with the Sisters at one school fostered connections with the other two schools. While a human link was there for the other two schools, leaders at these schools were understandably wary about strangers coming in from abroad. While they kindly welcomed us, there was still a period of “We’ll see how this goes, and we don’t want this visit to disrupt our daily work.” The onus was on our group to demonstrate to school personnel that our presence would be supportive of the schools’ missions while minimizing disruptions to their usual routines (it’s probably impossible to eliminate disruption altogether… school children will certainly notice the strange fashions and mannerisms and accents of the foreign visitors). We have now had three separate visits, and as we have established trust and goodwill over time, I have noticed that our partners have trusted our visiting teachers with enhanced responsibilities on each trip.

2. Follow your partner’s lead. As suggested in the previous paragraph, it is very important for American visitors to fully respect that their partnering school has important work to accomplish with its students, has an institutional culture that resides within a national culture, and has daily routines and expectations. The best way to be an ugly American (and wear out your welcome) is to disrupt all of that by walking in to a school and telling your hosts what you’ll do in order to “serve them.” The best way for your group to be of actual use is to ask your hosts what you can do to help support their mission. This can be tricky during the early phases of your relationship because your hosts won’t be completely sure of the kinds of services your group might provide or the kind of experience your group hopes to have. Therefore, it can be helpful to share ideas about the kinds of things your students might do at the school (such as providing afterschool tutoring, serving as teacher’s aides, organizing supplemental lessons focused on content of the school’s choosing, etc.) even as you emphasize that your students are willing to serve in any way that will support the school’s mission while minimizing disruption.

2. Follow your partner’s lead. As suggested in the previous paragraph, it is very important for American visitors to fully respect that their partnering school has important work to accomplish with its students, has an institutional culture that resides within a national culture, and has daily routines and expectations. The best way to be an ugly American (and wear out your welcome) is to disrupt all of that by walking in to a school and telling your hosts what you’ll do in order to “serve them.” The best way for your group to be of actual use is to ask your hosts what you can do to help support their mission. This can be tricky during the early phases of your relationship because your hosts won’t be completely sure of the kinds of services your group might provide or the kind of experience your group hopes to have. Therefore, it can be helpful to share ideas about the kinds of things your students might do at the school (such as providing afterschool tutoring, serving as teacher’s aides, organizing supplemental lessons focused on content of the school’s choosing, etc.) even as you emphasize that your students are willing to serve in any way that will support the school’s mission while minimizing disruption.

3. This is a practicum, not a mission. The problematic nature of “service learning,” particularly in the context of the developing world, is well-documented (the classic document “To Hell With Good Intentions” says enough). It is vital, then, that overseas programs such as ours ensure that participants properly understand their place as interloping visitors kindly welcomed as guests with a rich opportunity to learn (not generous saviors selflessly traveling in order to help others learn).

In order to send this message, we have found it helpful to emphasize with both our participating students and our partnering schools that we view this experience as being akin to the pre-student teaching practicum experiences our students are required to complete as part of their teacher education program. The parallels between the two experiences are many. In a practicum, the cooperating teacher is the expert while the student teacher is the novice seeking to learn via a combination of observation and small-scale practice. This is certainly true in Jamaica as our participants learn by observing and working with experienced teachers there, even as they have some opportunities to practice teaching with Jamaican students. In the practicum, it is understood that the presence of a practicum student represents a short-term drain on time and educational quality (that is, practicum students take time from cooperating teachers, serve as mild disruptions to the usual routine, and it is well known that the K-12 students will receive better instruction from the veteran teachers rather than the student teacher), but schools take on practicum students because doing so serves another important mission (it nurtures the teaching profession). Again, the same is true in Jamaica: our pre-service teachers detract something from the schools’ time and educational quality, but our Jamaican partners also recognize that the partnership can serve another important mission (fostering international understanding and providing their students with in inter-cultural encounter). Finally, the practicum provides real-world learning and legitimate teaching experience for our candidates. The same is true of the Jamaican experience.

4. You can teach this. As argued in my essay above, an overseas partnership can contribute strongly to an educational program aimed at developing racial consciousness. Items 1-3 above focused on the nuances of fostering such a partnership, but the challenge of teaching a relevant course aimed at preparing students to travel and developing a justice-mindset remains. This may seem daunting, particularly if your disciplinary training is unrelated to cultural studies or social justice. Here are two suggestions intended to encourage:

Consider Co-Teaching: Our Jamaica Program has always been a co-taught experience. I believe this has been a positive aspect of the program for both the co-teachers (who can avoid the perceived pressure of needing to be the “expert on everything”) and the participants (who benefit from the unique perspectives of multiple instructors). For the first three iterations of the program, I co-taught the experience with a music/music education professor. His contributions enriched our class tremendously. As elaborated in this essay, reggae music provided vital texts for our program, so it was a boon to have a musician in the room who could elaborate on the nuances of this musical form and its development over the past 60 years. He brought more to the class than his musical expertise, though. He had traveled to Jamaica many times and had studied its history extensively. With the music professor’s upcoming retirement, a new co-teacher (an elementary education and literacy expert) will join me as co-teacher. I am excited for the fresh insights and new expertise she will bring to the program. She already has a strong knowledge of Caribbean children’s literature, and she is currently diving into linguistic study of the Jamaican Patois. It is apparent that I will be learning at least as much from her as our students will. Furthermore, having two education professionals in the program has been very helpful in terms of supervising our college students at the Jamaican school sites.

Your overseas partner can also be a powerful co-teacher. Partnering teachers and administrators will obviously be teaching your students when you are on site, but you can also involve them in the pre- and/or post-trip programming as well. Possibilities abound: schedule a Skype session between them and your class, ask for their reading recommendations, arrange for pre- and/or post-trip “pen palling” between their students and yours, etc.

Consider Co-Learning: It is understandable that an instructor with relatively little knowledge of another culture would feel unqualified to teach a course aimed at helping students develop an understanding of that culture. As I have already suggested, though, it really is impossible to develop understanding of any culture in the context of single college class, even if experts are teaching the course. The best that can be hoped for is that students will begin to develop their understanding. If you are willing to abandon the role of “expert,” and acknowledge that you are beginning to learn even as your students do, you could well find yourself leading the experience quite competently. You can model the process of mature learning by avoiding hasty assumptions, asking ongoing questions, and modeling mature ways of pursuing questions. If you are willing to dive in as a co-learner leading the class, though, I would strongly encourage you to lean on your international partners for suggestions about material to use in the class.

Of course, the language of the host country is another complicating factor. Partnering with a school that has English as the language of instruction is likely to make the experience less intimidating to prospective teachers and student participants alike.

5. Resources. Resources are an ever-present and wide-ranging challenge. Start-up funds are one challenge, but other resource issues will pop up as well: will instructors be able to fit this into their teaching load, is there room in the curriculum to introduce a new course that will attract students, will students be able to afford this experience, etc.? I cannot know what the resource limitations will be at any given institution, so I won’t make any promises that you’ll be able to find a way to get an international program going. I will share information about how we have navigated the resource issue with the hope that parts of our story will be helpful to others.

We worked closely with our institution’s Office of International Programs in launching the program. Most institutions will have a similar administrative office, and we found their services to be very helpful. It is hard to enumerate the ways that they helped us: from seed money for a planning trip, to helping us set a budget and participant price tag, to providing helpful checklists of things to attend to (immunizations, passports, registration with the State Department, etc.), and on and on. Your campus likely has support personnel that can guide you through the many details of planning and implementing an overseas program, so start with them.

In terms of curricular considerations, we have found it helpful to situate our Jamaica program within our college’s general education requirements rather than within a specific major. We teach at a liberal arts college, hence our institution has fairly substantial general education requirements for all students. The coursework associated with our Jamaica program corresponds to two graduation requirements (Global Diversity and Perspective on Human Values), a fact that provides extra incentive for some students to participate. As I noted earlier, one positive to housing this program outside of the teacher education major is that it opens up space for students to examine schooling for a critical perspective. However, as a general education course the course is also open to all students (not just education majors) and has no pre-requisites. This could potentially be a negative as instructors have less certainty about what students will have studied prior to the course. In our experience, though, this has not been an issue. The vast majority of our students have been education majors taking this course as an elective, and all participants (regardless of age or major) have brought valuable knowledge and experience to bear as we all learn together as a classroom community.

The instructor’s teaching load is another important resource consideration. Indeed, depending on the institution, this could actually be the most challenging hurdle to overcome. My colleagues and I certainly benefit from teaching at a liberal arts college. Our college values the general education program and encourages departments to contribute courses to its curriculum. So, we certainly had institutional support in creating a general education course that is available to all students on campus. Not only does our institution support general courses, but the reality is that the number of teaching majors we need to serve has been falling over the past decade. We are not immune to this national trend, hence education faculty at our institution have gradually had less required work in the teacher education program, opening up opportunities to teach students in different ways.

Incredible post Brian, and an amazing program. Thanks for doing this (both the post and the program). I never thought I’d see Queen Nanny, Marcus Garvey, Buju Banton, or Sizzla shouted out in a math post. This post also reminds me of the opening line of the biggie smalls platinum selling single Juicy. “This album is dedicated to all the teachers that told me I’d never amount to nothin’.” His scars from the educational system must have ran so deep to make that kind of statement. Beyond that, the fact that so many young people from around the US identify with that statement says a lot about our educational system.

Thanks for the kind words and bigger thanks for that gem from Biggie.