Last week, Bates hosted speaker Susan Burch, from Middlebury College, for a workshop called “Learning for EveryBody: Inclusive Teaching and Curricular Practices”. I was lucky enough to be able to participate in the interactive session and later have dinner with the speaker, and in this post, I wanted to first share some of the main ideas from the workshop, and also some of my own ideas on how this could be applied to the mathematics classroom.

Last week, Bates hosted speaker Susan Burch, from Middlebury College, for a workshop called “Learning for EveryBody: Inclusive Teaching and Curricular Practices”. I was lucky enough to be able to participate in the interactive session and later have dinner with the speaker, and in this post, I wanted to first share some of the main ideas from the workshop, and also some of my own ideas on how this could be applied to the mathematics classroom.

First, Burch explained that there is a difference between barriers to learning and individuals. Instead of blaming individual students for their differences (perceived sometimes as shortcomings) we need to accept that there are barriers preventing them from learning instead. “Individuals are not problems.” In that sense, she wanted us to think about curricular practices that are inclusive and equitable, rather than focus on the specific diagnostic level of “how do I deal with a student with _____”. In a way, she invites us to think bigger. (Here is a useful link to the main social identifiers commonly used to talk about “differences” and diversity.)

She also share with us her version of this wonderful access statement that Margaret Price uses to begin all of her talks. I really appreciated it when I heard that we were invited to use the space available “in whatever way is accessible to you. For example, you may want to move around; stand up; lie down; put your feet up; go out and come back in; stim; engage with another person (for instance, by writing a note to a friend); tweet; take notes; or any other use of this space that feels right to you. Knitters, feel free to take out your work! If I was able to knit and deliver a talk at the same time, I’d be doing it.” Especially since I often feel that taking out my knitting would be “rude”, but it helps me with my general fidgetiness and actually helps me focus. This invitation already made me feel included and safe. Too bad I left my knitting at home!

(From the Utah Education Network page.)

Burch gave us two main guiding principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and anti-oppressive teaching practices: clarity (“robust learning and understanding depends on information being legible”), and choice and equity (“provide multiple methods of representation, expression, and engagement — using different approaches that respond to the different ways people acquire and express knowledge fosters equity: it reduces the tendency to privilege certain kinds of students over others”).

So how do we use these principles when we’re developing and then teaching a course? The workshop was divided into two parts, each exploring one of the main principles outlined above.

Clarity

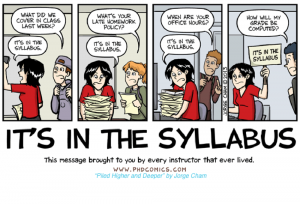

Maybe if you have to repeat this all the time, you’re not being as clear as you think?

In terms of curricular development, Burch claims that most of the work should happen before the semester starts. We should share our syllabi, and these in particular should contain learning outcomes and goals, policies, any important timelines, timing of assessments, and clear break down of the grading schemes, as well as any course-related materials (like textbooks, websites, programming languages, etc). In my own courses, I usually have two sections called “Course Promises” and “Course Expectations”, but I don’t think I’m as explicit as I could be about what those mean and why they are there. I wrote about syllabus-writing in my previous blog life, but I think this workshop made me realize I am not nearly as transparent about things as I think I am.

Then Burch told us about how to incorporate clarity into our teaching. There were a couple of things that I already knew about, especially after reading Darryl Yong’s recent, wonderful MAA Teaching Tidbits blog post on “How Transparency Improves Learning”. But there were a few pleasant surprises in there that I’ve been thinking of incorporating into my next class ever since. For example, setting classroom agreements, in particular social ones. What happens when we disagree? How do we use the class time in ways that are sustainable (for us)? How do we want to be called/what pronouns do we use? She was very clear that the last one needs to be done only with consent, and we need to give students the choice not to disclose their pronouns. One of the things she mentioned was that by knowing students’ names (she suggests having nameplates for people who have trouble remembering names) we don’t need to use pronouns as much anyway.

In terms of how we approach disagreement, you might think it is more common in say, an American Studies course like the ones Burch teaches, but in many of my classes I have students present solutions and interact with each other, and I think we could all benefit from establishing rules like these. I definitely think it would make more students more likely to participate if they felt like there were agreed upon rules of behavior, and all discussion would be less about critique and more about being part of a learning community.

Lola Thompson, from Oberlin College, has her students write textbooks as an end-of-semester project with all the proofs they’ve written in the course. This particular student was also taking a book-binding class, so don’t expect this level of professionalism from everyone! (However, how great that this student had an outlet for her artistic side in her Number Theory class!)

One caveat: transparency does not mean handholding or coddling. An important thing about clarity is to establish which of these tasks are the student’s responsibility (this is my “course expectations in a nutshell”). The “agreements” at the beginning of the semester can work as a reminder of this. For example, in my team-work heavy courses, I have the students write a team contract at the beginning, stating clearly how they are going to keep each other accountable and also support each other.

Another idea that I really liked, and have used somewhat, was the idea of crowd-sourcing note-taking. She even modeled this at the beginning of the talk by asking for note-takers, and then creating a google doc where we could share our notes about her talk. She said she usually asks for a few note-takers at the beginning of class (I think she said four or five), these notes are shared on the class website or google drive, and can be edited by anyone (and spot-checked by the instructor, to make sure there are no glaring misrepresentations of the material). This is great for students with learning differences who need note-takers (you take the burden off your accessible education office by not asking to hire a specific student for this task), but it’s also great for someone who had to miss class due to a concussion (a common occurrence at Bates) or other illness. This gives students several sets of notes to look at (or one, multiple-edited resource) and encourages students to treat each other as shared learners. It can also be a way for students who are introverts or shy to earn a participation grade without having to speak up in class.

A screenshot of the Piazza page I had for Number Theory class two years ago. I would make this less homework focused and more holistic next time.

I have done something like this in my Inquiry-Based Learning courses, where students can share proofs presented in class on our Piazza page. But it was always optional and an alternative to class presentations for earning a participation grade, and Burch’s talk makes me think that it could be even more integrated into the course. I have colleagues who have made their classes create class wikis and class textbooks, so I will probably be bugging them about this soon.

Choice and Equity

My Bates colleague Katy Ott had her Real Analysis students do a “meme” project tagged #thestruggleisreal. It is a way for students to be creative and digest math for popular consumption, and also to vent a little bit (because Real Analysis is hard!) (Meme courtesy of Matthew Goldberg.)

In terms of curricular development, choice and equity means that we “have different ways to share knowledge, acquire knowledge, assess knowledge, and demonstrate command of knowledge. ” For example, in terms of different assessments and activities, you could have papers, student poster presentations, short, online writing assignments, group work, and student presentations. I already do combinations of these in my classes, but I think I can be much more explicit and transparent about why I’m doing this, to the students and to myself. It is not a stretch to think of mathematics in these different contexts, especially since we DO mathematics in many different ways: individually, with computer experiments, by talking to each other, writing papers, giving talks, etc.

Burch cautioned us against our “ideal student bias”: we tend to privilege students who are like us. For example, in my case, I definitely was the kind of student who was happy to sit in the back and work on stuff on my own, even if I didn’t get much out of a lecture. I did not like speaking up, but I was a “good” student because I did well on exams (the main way in which I was evaluated). I taught like that for much longer than I care to admit, until I realized how many students were falling through the cracks, students I could recognize as genuinely talented and interested. Things have been much better since I have been switching things up a bit, and I tell them clearly why I’m doing all the different things I’m doing. For the most part, I think they appreciate this.

One thing I could do better is in terms of ableism. I definitely privilege students who are more like me (even those who like me struggle with depression and anxiety — I’m much quicker to spot and support that than other challenges). For example, I had for a long time been doing Inquiry-Based Learning, and class time mostly involved students coming up to the board to present their work. It wasn’t until I had a very bright student with some mobility impairments that I realized this was not the same experience for everyone and definitely not a fair way to assess my students (not to mention the fact that for the one visible disability I encountered, there were probably many invisible ones I didn’t even think of — like the student who came to me at the end of the semester to say he didn’t participate too much because he was very allergic to chalk!). This was another reason I started doing the Piazza proof-writing as an equal participation grade, and again, I think it has improved the experience quite a bit.

In my Great Ideas in Mathematics class this semester, we explored concepts in cryptography by doing an escape room activity (inspired by a similar activity developed by Anne Ho at Coastal Carolina University.)

In terms of how to ensure choice and equity in our teaching, the message was very similar. We need different ways to share knowledge: videos, lectures, small group discussions, listening to radio or podcasts, visiting places. Again, I try these to some extent, but I hope to become more intentional and clear about why and how I’m doing this. In particular, I hope to think about ways of teaching that do not come natural to me (like going outside the classroom).

I recently adapted an activity developed by my friend Anne Ho (Coastal Carolina University) in which the students work on cryptography concepts through an escape room activity. It was extremely difficult to develop (and had some flaws of execution) but I think it was a great way to switch up my usual active learning (which is mostly worksheets to be solved in class).

Finally, I want to say that a lot of what I liked about Burch’s workshop was that it was, in fact, interactive, and the guiding principles were actually put into practice throughout. We had breakout sessions where we explored how we would apply these ideas to our own teaching, we looked at people’s sample syllabi, and we worked through some difficult questions about whether some activities we were doing were not inclusive/equitable enough. She even started with the wrong slideshow, realized this three slides in, and changed it, all the while pointing out that at that moment she was modeling “flexibility”! I also liked that much of this felt like validation/confirmation of things I already knew and did. This past semester was a tough semester, with lots of experimentation (some of which worked, and some which did not), so it was also good to hear that these changes are incremental, the process of making our classes more inclusive and equitable needs to be sustainable, and that not all the changes will happen at once. There will be error and failure in any new process, and we need to learn from that and keep going.

So, dear readers, what do you do in your classes in terms of these two guiding principles? What would you like to try? Or, alternatively, what would you have liked your teachers to do when you were a student? Please share your thoughts with us in the comments section below.

And if you’re interested in reading more about these ideas, here are some additional resources:

Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) : A resource on UDL and technology in the classroom.

National Center for Universal Design for Learning

UDL Strategies: Has specific resources for math classrooms.

The MAA Instructional Practices Guide: Has a chapter on Design Practices with a subsection on UDL.

You can read more about universal design in a section of the newly-released MAA Instructional Practices Guide! Comments are still sought on the Guide.

https://www.maa.org/programs/faculty-and-departments/ip-guide

I use a LiveScribe Pen in class. It’s a pen with a tiny camera in the tip and a microphone, and it produces PDF notes from the class that are synched with the audio in extremely helpful ways. The students pass around the pen and take notes, but because of the audio, it’s low stress. When students have had “Accommodations letters” (as they are called on my campus), they say these PDF notes are perfect. Students with chronic illnesses and students who are English language learners are very excited about this resource. I think this is universal because it helps everyone and raises all students to a level playing field, without singling out student differences.

http://www.livescribe.com/en-us/solutions/learningdisabilities/

I also like to do individual oral exams, in part because it addresses “extra time” and test anxiety phenomena in a similar way.