I have written in other public fora that math is not apolitical, that the implicit messages in our silence on these issues is damaging to students,  and that mathematics has particular bigoted elements in its history and present framing that we must engage actively. In light of the attention being drawn to white supremacy and the related terrorism in part due to last weekend’s events in Charlottesville, I am planning on opening the discussion of these themes on my first day of class next week. In this post, I will discuss 10 ideas for starting this conversation, explain 3 more detailed lesson plan case studies, and list resources shared with me by others. Readers are encouraged to comment with their own ideas, so the list of resources will grow.

and that mathematics has particular bigoted elements in its history and present framing that we must engage actively. In light of the attention being drawn to white supremacy and the related terrorism in part due to last weekend’s events in Charlottesville, I am planning on opening the discussion of these themes on my first day of class next week. In this post, I will discuss 10 ideas for starting this conversation, explain 3 more detailed lesson plan case studies, and list resources shared with me by others. Readers are encouraged to comment with their own ideas, so the list of resources will grow.

Some people, including both students and educators, have suggested that math class is not compatible with discussing justice or diversity. While I reject this assertion and think I’ve refuted it in the links above, I am left without many established models for doing this work. There already exist useful resources lists for doing this kind of work under the hashtags like #CharlottesvilleSyllabus or #CharlottesvilleCurriculum, but most of these tools are for general purposes once the topic is opened. Given the perceived disconnect between math and discussions of identity and equity that some of my students bring to class, I am instead trying to open this conversation in a way that is specific to math. In particular, I think I am more likely to be effective in this work if I can help my students see these discussions as naturally connected to and appropriate for my courses.

In this post, I’m going to describe the kernels of ideas I have for this opening connection. I am definitely not the expert in either making these connections or leading the opened discussions, but I have ideas that might be useful. I encourage you to comment below in order to share other kernels.

My context is specific and peculiar, as is each of ours. In an effort to support generalizations of these ideas, I’m going to organize them around the aspect of the course/discipline that I’m connecting with justice or bigotry.

Pedagogy and course design: I’m going to explain the way I think learning works, so I can easily mention that part of the decision-making process involves thinking about whether it disenfranchises some students. Similarly, the work in my classroom is going to be powered by collaborative effort on tasks that are too challenging for individuals and that require multiple perspectives for optimal outcomes. In other words, this course requires diverse perspectives and will demonstrate that this outcome is more than the sum of its parts, and so is our society.

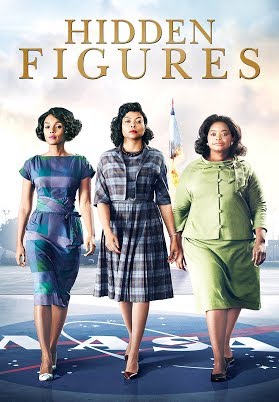

Diversity in the discipline: Several groups of people are underrepresented in our discipline.  I can connect this issue to my students’ futures, talking about what we can do to address this problem, starting with our classroom. With the visibility of the film Hidden Figures, there’s also a chance that students are aware of the need to look for mathematical expertise outside of the ranks of white men. Profiling a particular mathematician (and assigning students to do other profiles during the term) opens the door on discussions of the barriers placed before some people based on demographics.

I can connect this issue to my students’ futures, talking about what we can do to address this problem, starting with our classroom. With the visibility of the film Hidden Figures, there’s also a chance that students are aware of the need to look for mathematical expertise outside of the ranks of white men. Profiling a particular mathematician (and assigning students to do other profiles during the term) opens the door on discussions of the barriers placed before some people based on demographics.

History of the discipline: Proof writing is revisionist history, and the western view of math as ahistorical implicitly supports white and male supremacy by making other contributions invisible. Talking about the disciplinary narratives can open up that discussion. I think that the racism and intellectual imperialism themes in The Man Who Knew Infinity are particularly powerful and may be accessible through clips of the film. Similarly, there are historical figures in math who used to loom large but whose legacies are being reconsidered; talking about these movements offers a connection to the movements that seek to move statues of Civil War generals from pedestals to more thoughtful critiques.

Equitable access for students: College is seen as a bottleneck for people who seek prosperity and other forms of respect, and math is seen as a further bottleneck within this context. Reframing the course around success for all is an opportunity to counter the supremacists’ claim that access for more people would mean either lower standards for all or fewer resources for those who are privileged by the status quo.

Content: If I’m going to consider an application or foundational example from the course, the context could just as easily be about topical issues.  Reason quantitatively or statistically about incarceration rates; model rates of change in family wealth; consider the logical structure of a statement about racism; talk about important challenges in the world that require the skills from your course. Vi Hart has some nice videos that use mathematical concepts to discuss current events.

Reason quantitatively or statistically about incarceration rates; model rates of change in family wealth; consider the logical structure of a statement about racism; talk about important challenges in the world that require the skills from your course. Vi Hart has some nice videos that use mathematical concepts to discuss current events.

Personal experience with the discipline: Lots of us have struggled with math and felt that the system rejects us, and the rest have seen this system treat someone we care for terribly. My graduate program was notably more diverse than others, in part because of efforts by faculty like Karen Uhlenbeck, but I have plenty of stories of fellow grad students being treated as incompetent based on gender or race and birth country.

Institutional history and local data: My students find local data and stories specific to this institution to be particularly compelling. We are significantly more diverse than we were even five years ago, though there certainly have been racist backlash events on campus. This year, we have a huge increase in the size of our international student population. I could engage the college-wide common readings and the institutional mission statement. In terms of a historical, mission-centered story, this Lutheran-affiliated college had an interesting reaction to the Scopes “monkey trial”: college leadership announced that taking their faith seriously meant looking at the world rather than assuming they knew it, so they established a department of Geology. I’m sure there’s a way to use this story to make space to discuss rejecting domestic terrorism today.

Policy statements: Leading professional organizations, including the MAA, AMS,  CMBS, and NCTM, have made statements either overtly about equity and justice in our field or that are grounded and justified by these concepts. Discussing these or quoting them on a syllabus is a powerful way to connect a conversation from one classroom with larger disciplinary norms.

CMBS, and NCTM, have made statements either overtly about equity and justice in our field or that are grounded and justified by these concepts. Discussing these or quoting them on a syllabus is a powerful way to connect a conversation from one classroom with larger disciplinary norms.

Epistemology of the discipline: Viewing math as universal and absolute is a double-edged sword. Overtly, it suggests that all are welcome in math regardless of demographics and identity. In practice, this also means that the identity of white and male has been allowed to step into the position of “normal” without question or resistance (or even being seen as a step) while caring about or having any other identity is excluded, making the environment hostile. If the universality is shifted back to the ability of anyone to make arguments with the awareness that these arguments are judged and valued by groups of people, we can perhaps help math live up to its utopian ideals. The false equivalencies of the status quo and this intentional reformulation has strong parallels to the corruption of the founding ideals of the United States by white nationalists and their reformulation by more progressive thinkers (including James Baldwin’s excellent “The Fire Next Time”).

Other course components: Put these ideas in the syllabus and make sure the students read it. Send a pre-course reading, but make sure you scaffold students in reading it. Survey your students; even asking students their pronouns signals that you resist normative oppressions. Ask them to write a MathBiography about their experiences with and identity in math. Embed ongoing reading and reflection in the course. I would suggest “Teaching Mathematics with Women in Mind” and the Myth of Genius for gender and have heard good things about “Weapons of Math Destruction”. I would also recommend this presentation by Dave Kung about diversity in the discipline, perhaps more for us than for students. My list of readings for students related to race is sadly thin.

Before I conclude with three lesson plans as case studies, I need to make two points:

- I am tenured and I present as a white male to students who have just met me. My actions (or my silence through inaction) is filtered through this positioning. My privilege gives me a strong position from which to insist that we discuss these issues, my positioning may mean that the students who most need to rethink their privilege might listen to me because they think I may be like them, and my silence (were I to choose it) would be validating for the status quo and hurtful to those who most need support. These factors are different for different faculty, and I am certain that these differences impact instructors’ options for engaging these topics.

- The ideas above vary in goal and depth of engagement with issues of identity, justice, and bigotry. Some send strong signals to vulnerable students that you are an ally but may slip past other students unnoticed. Some help establish classroom norms that resist bigotry but function without overt reference to white/male supremacy as they go forward. Some bring students’ thinking to the surface or even seek to teach/change them actively. My sense is that we want all of these elements in our courses and that we want them spread intentionally across the course for sustained impact. I do think that the distribution will depend on the context.

Case A: 1+1=2

One of the derisive comments on some of my previous writing used “1+1=2” as an example of a patently, in the commenter’s mind, apolitical math, trying to show that I was off base. I disagree.

- Historically, this kind of algebraic notation for

arithmetic was brought to Europe from the Arabic-speaking world through trade across the Mediterranean (attributed to Fibonacci by some). This mathematical sentence is an artifact of both human invention and inter-cultural communication.

arithmetic was brought to Europe from the Arabic-speaking world through trade across the Mediterranean (attributed to Fibonacci by some). This mathematical sentence is an artifact of both human invention and inter-cultural communication. - In order to make meaning of this number sentence, most people need to think of actual objects: one apple and one orange makes two fruit. This act of objectification is very powerful, and it is a human act, not a universal. The fact that you all know the phrase “the whole is more than the sum of its parts” means that there are contexts in which this kind of objectification is not appropriate or most useful, so it represents a choice and hence power. A bit more subtly, I suspect that the ways we map sentences to their logical structures in set theory can quietly reject certain kind of concepts. Intersectional feminism was born from the idea that discrimination against a black woman need not be simply general racism or general sexism.

- The equal sign has its own history as a symbol, but it also has a very complex life now. Sometimes it means that two objects are equivalent. Sometimes that one object is defined in term of another. Sometimes it encodes a restricted domain for another function. Sometimes it’s an order to compute, others a command to solve for an unknown. One of the most challenging aspects of elementary and secondary mathematics is coming to integrate these multiple conceptions and to select the appropriate one in each context. One of the ways we track students out of the discipline is by assuming that inaccurate interpretation of this complex symbol is purported evidence of incompetence (despite the fact that some students have no systematic support for integrating these interpretations). This is a tool of denying individuals access to power; it’s the handshake of our secret society.

- And in practice, the number sentence is used by people for doing and communicating math, and any time there are groups of people involved there is power. Moreover, the narratives around which ideas are important are tools for building and maintaining power. How many of our departments contain any mathematics from the non-Western world? And those that do, how many frame it as a single course in non-Western or ethno-mathematics, with the implicit othering in this labels?

So, while “1+1=2” references a (potentially) universal truth, as groups of humans we interact with these linguistic representations and cognitive moves, making this string of characters far from “apolitical”.

Plan: Write “1+1=2” on the board. Ask students what it means, how they know that, and what assumptions they had to make in order to come to that conclusion. Be prepared to draw themes like the above from their observations.

Case B: “Student Names”

I learn my students’ names as they enter class on the first day. I use various learning strategies, and I ask the students to move around and change their appearance in order to give me more challenging and realistic testing situations.

Then I ask one of the students to name all of their peers. They can never do it (at least in my ~20 person calculus courses). I use this moment to ask them what I did to learn their names, and then I ask them if they want this to be a class in which they watch me do these things or they do them themselves. They always vote for active learning.

Then I ask one of the students to name all of their peers. They can never do it (at least in my ~20 person calculus courses). I use this moment to ask them what I did to learn their names, and then I ask them if they want this to be a class in which they watch me do these things or they do them themselves. They always vote for active learning.

Then we move to them learning peer names. I usually ask them to alphabetize by the name they wish to be called in class. (This task is purposefully ambiguous to model the expectation that this course will require collaborative effort and group decisions. It also implicitly suggests that they will be moving around in class.) This year, I’m thinking of pointing out that they never even discussed which alphabet to use for this ordering.

Once they are ordered, they introduce themselves as well as everyone who has already been introduced before them (in the style of an ice-breaker). I model other aspects of group discussion facilitation. This certainly communicates that they need to know their peer’s names, and we reflect on the assumptions about active learning that I’m instantiating with the exercise.

Almost every time, one of the students uses a gendered pronoun to refer to a peer, despite the fact that it’s counter-valued by the task. I will take this moment to point out that it’s inappropriate to gender a person without knowing their pronouns. Sometimes a student will say something with a cultural component that gets treated inappropriately, and I offer a revised statement. In this moment, I talk about why that kind of mistreatment is at odds with the values of this classroom and the beliefs about learning that power it.

I plan to end this activity with overt discussion of these themes, grounded in the pedagogical choices for the course. In the past, having these discussions early allows me to connect ongoing events on campus (like #BlackLivesMatter protests on campus) to the values of our classroom.

Case C: Open Questions

I ask my students to introduce themselves on the first day of class and to reflect on their beliefs about our discipline through a MathBiography.  I usually do my own introduction via a prezi entitled “Mathematics (Mis)Conceptions”. The prezi helps students see some of the philosophical questions about the field that excite me and also to view the field as a living discipline rather than a collection of facts. Students find these ideas very interesting but also destabilizing. In this destabilized state, I think they will be receptive to other questions: in what ways are these beliefs contributing to the exclusion of some groups of students from the field?

I usually do my own introduction via a prezi entitled “Mathematics (Mis)Conceptions”. The prezi helps students see some of the philosophical questions about the field that excite me and also to view the field as a living discipline rather than a collection of facts. Students find these ideas very interesting but also destabilizing. In this destabilized state, I think they will be receptive to other questions: in what ways are these beliefs contributing to the exclusion of some groups of students from the field?

My plan: If I had to teach this first class right now (rather than on Monday), I would start with the name-learning activity and discussion of values (pedagogical and otherwise) for 45 minutes, do my own introduction with the misconceptions prezi for 15 minutes (without the final question), ask them to think about and discuss 1+1=2 for 10 minutes, and then return to the final question from the prezi for a 5-minute wrap up that explicitly connects with the events in Charlottesville if those connections haven’t come to the surface already. The plan is still a draft.

- There is No Apolitical Classroom

- Seven Ways Teachers Can Respond to the Evils of Charlottesville

- The first thing teachers should do when school starts is talk about hatred in America.

- Resources for Educators in the Wake of Charlottesville

- Fact Check: What about those other monuments? Trump’s question answered

- How “Nice White People” Benefit from Charlottesville and White Supremacy

- The Painful and Liberating Practice of Facing My Own Racism

- Invisibilia

- Are You Sure You’re Not Racist?

- Threads related to this tweet by Django Paris, author of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies.

Thanks for your post, Brian! You might find some of my writing from a previous project helpful. I explored the racism connected with the sequence of counting numbers (1, 2, 3,…), the assumptions made about them, how they are connected with ideas about development and civilization, and so on. I wrote a short feature article on this work for New Scientist (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(11)60869-5 ; email me for a copy if your institution doesn’t have the right subscription for that), and a full scholarly version in the British Journal for the History of Science (http://mbarany.com/SavageNumbersBJHS-FirstView.pdf ).

A few friends have observed that there is a second barrier for mathematicians thinking of discussing justice in class: they don’t feel equipped to lead those discussions. Two thoughts:

(1) In similar contexts, students of color on my own campus routinely say that it matters more to them (right now and in the moment) that their instructors say something than that they say the perfect thing. In other words, you aren’t choosing between saying the right thing and saying the wrong thing. You are choosing between saying something and saying nothing (though that silence speaks loudly). It’s fine to say that you aren’t sure what would be best to say, once you start speaking.

(2) I teach all of my courses with inquiry. In these classes, I bring student thinking to the surface and then facilitate discussion in order to leverage that thinking and the collective attention to change minds. I claim that this is exactly the same skill set needed for discussing justice. I see strong connections between my classrooms and those of my colleagues in the Humanities, just with slightly different content sometimes. I know it’s still scary, but you are human adults, so engaging these conversations as engaged people, when combined with your pedagogical experience, does make you equipped to start this work. Of course, there is specific expertise that you will develop by doing it and by learning about how others think about doing it, but you don’t need a terminal degree to start.

Wonderful post BK! I look forward to hearing how the course goes.

Hey Matt! This is awesome. I too want to hear how the course goes. Brian, will you do it in all of your courses or just calculus?

Nicole, I am only teaching Calc this term, so they are the same. The name+pedagogy activity requires a big enough group of students who don’t know each other, so I do it in my lower-division courses but not the upper division ones. I usually do something philosophical/epistemological in my upper-division courses, so I would lean more heavily into the prezi in that context. I also teach courses primarily for future teachers, and since justice is a core value of people interested in being in the public schools, thinking about that particular context can be powerful (though all students have experienced school before, so sometimes I can get at this angle with reading like Lockhart’s Lament even if the class isn’t entirely filled with future teachers).

And I’d be happy to follow up. In person, I attend JMM, RUME, and MathFest most years.

Anonymous:

In reading your blog I was reminded of the “rhind” papyrus, named not after the great Egyptian mathematicians who created it, but after the person who purchased it, and which is now in the British National Museum. So many histories that have been erased, many times intentionally.

Your reference to hidden figures reminded me of Roxane Gay (“bad feminist”); she has has created a categorization of films, I am not recalling all the categories, but the one that I recall the most is the one that includes movies that are for the “enlightenment of the whites.” Movies that use the plight of the African Americans for the enlightenment of the whites who tend to be portrayed as either as stupid, or blind, or mean. The movie is not about African American accomplishments, but about how the whites in the movie (and by extension the audience) start to see things that they had the privilege of not seeing before. She asks, where are those whites? The Help and Hidden Figures are in this category (which is for me super revealing as I liked those movies a lot… I guess I have a lot to learn)

Unfortunately, the great Egyptian mathematicians who created the Rhind papyrus remain unknown. The scribe is mentioned in the papyrus, and the papyrus is sometimes named after him, the Ahmes papyrus. It seems that the ancient Egyptians thought less of authorship in this context than modern academics.

Most sources discussing the Rhind or Ahmes papyrus mention the role of Ahmes as the manuscript’s copyist, so it is hard to argue that this aspect of its history is erased. Indeed, its Egyptian provenance is readily apparent from usage of the term “papyrus”.

Ancient Egyptian society was based on slavery. Egyptian mathematics was a tool of governance for the Egyptian pharaohs, and is thus complicit in civil rights abuses. Why are you hiding this history from us, intentionally misleading the reader into thinking that Egyptian mathematical papyri are not about ancient means of exploitation?

I want to add one additional reference to Brian’s excellent article. I have used the book “Loving and Hating Mathematics: Challenging the Myths of Mathematical Life” (http://press.princeton.edu/titles/9283.html) in some of my courses as a way to introduce discussion about mathematics and social justice. I have found that it is often easier for students to enter into conversations about these things when the catalyst for the discussion is external (e.g. passages in a formal text), and this helps me prevent the course from getting bogged down by resistance from students who feel that I’m imposing my “personal opinions that aren’t math” into a math course. Several of my colleagues used Francis Su’s “Mathematics for Human Flourishing” https://mathyawp.wordpress.com/2017/01/08/mathematics-for-human-flourishing/ in a similar manner last Spring.

Love it. I have a large and expanding list of non-white-male mathematicians available for any interested in profiling some for their classes. Maybe even making it a ritual weekly occurrence…

https://arbitrarilyclose.com/2016/08/21/the-mathematicians-project-mathematicians-are-not-just-white-dudes/

I would love to see it! Nicole.m.joseph@vanderbilt.edu

This is a great post, thank you!

Of course, my first day of classes are already prepped… trying to figure out how much I can adapt / work in. I already have my pronouns on the syllabus & plan to make a point of giving them when I introduce myself.

I wonder if you’re willing to share your name learning strategies? This is always very hard for me. I feel like I’m making an effort, but clearly it’s not an effective effort. I joke about all of the “K” names (I had 13 of them out of 25 last semester) being at fault, but I know I can do better.

I don’t think I’m doing anything special with names, but here’s an overview:

As students enter, I ask their names, writing them on the board in a geometrically representative seating chart. [As all students what they want to be called and how to spell it, in part to keep from singling out students with names outside your culture group, but it’s just generally respectful] Once I’ve added 2-4 names, I give myself a mini-quiz on all of the names so far. Once the room gets close to full, I make sure to reshuffle the order of the quiz (eg columns instead of rows). At this point, I usually do a public version with the students all checking that I have their name right. Then I ask them to move around, and I repeat the quiz. [If I’m honest, some groups are easier for me. I definitely use hair color as a first separator.] Next I ask the students to move again (if I made a mistake) or to move AND change their appearance (outer-coats, hair up/down, switching an item with a peer). I do have reflect on the list of names after class, trying to summon an image of each student that night for the crammed pairings to stick.

Brian, where have you been all my life! I would have loved for you to write a chapter in my edited book on Interrogating Whiteness. I really would love to follow up with you. This is amazing work for our math community.

Brian, it is clear that you have done some good due diligence related to understanding different ways mathematics has excluded most that are not white and male, and ways in which math embodies white supremacy. I really would like to talk to you. I’m in math ed and have lots of colleagues in the mathematics field.

Great ideas, Brian! I know you are aware of the following, but I am sharing it in case anyone else in the community is interested. The Mindset Scholars Network, a group of well-respected researchers who conduct and disseminate learning mindset research, has identified 3 crucial mindsets: Belonging Mindset, Growth Mindset, and Purpose & Relevance mindset. The belonging and growth mindsets are perhaps the most germane to this discussion. In addition to growth messages, you can explicitly talk about the myth of, and the dangers of believing in, fixed intelligence. Recent research points to belonging as perhaps the most important mindset to help students develop, and it is quite relevant in a discussion of persons who are being discriminated against. I will create a second post with a little more information about the research base that shows just how important it is for students to feel as though they belong.

As you pointed out, context may dictate what an instructor feels is appropriate/safe to talk about. An instructor uneasy about directly addressing current events may be willing to do a belonging intervention or discuss the relevance of belonging in math classes. These interventions/discussions can be set up to address race/gender/etc. If the instructor gets in trouble, he/she/they may point to the overwhelming new research as reason for the intervention instead of relying on recent events as the primary reason. Of course, recent events may naturally surface, but education research conducted by leaders in the field backs the instructor’s choice. You can find relevant research at http://mindsetscholarsnetwork.org/, and the studies provided describe interventions that have proven successful.

The Mindset Scholars network has a page with links to fabulous additional resources (http://mindsetscholarsnetwork.org/research-library/additional-resources/). Most of the activity-based resources are about growth mindset, but the following focus more on belonging…

Mindset Kit belonging course for educators: https://www.mindsetkit.org/belonging

Web resources for belonging cues: https://www.mindsetkit.org/belonging/cues-belonging/resources-cues-belonging

Downloadable belonging activities: https://www.mindsetkit.org/belonging/cues-belonging/activity-cues-representations

Instructor reflection activities to support belonging: https://www.mindsetkit.org/belonging/about-belonging/activity-supporting-belonging-through-participation

Strategies to reduce stereotype threat: http://gregorywalton-stanford.weebly.com/uploads/4/9/4/4/49448111/strategiestoreducestereotypethreat.pdf

Tips on social belonging interventions: http://gregorywalton-stanford.weebly.com/uploads/4/9/4/4/49448111/getting_the_belonging_message_right.pdf

One to three-hour social belonging intervention (free to schools but may be limited access): https://www.perts.net/programs or http://collegetransitioncollaborative.org/#research

This has activities described and the articles related to the activities, but it would require more digging on the educator’s part: https://sparq.stanford.edu/solutions

For example, https://sparq.stanford.edu/solutions/help-groups-each-other-combine-them provides a description of a problem, a solution via a research-based intervention activity, and links to the actual article that discusses the intervention. You can go through the actual article to get more specifics about the activity.

This isn’t an activity, but it talks about how different subgroups may be affected by belonging interventions: http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org/2016/08/06/guest-post-response-from-david-yeager-to-my-question-about-sel-race-class/

A little more about belonging…

Much belonging research grew from the research on stereotype threat. “Stereotype threat is being at risk of confirming, a self-characteristic, a negative stereotype about one’s group” and, when aroused, it can be detrimental to academic performance (Steele & Aronson, 1995, p.797). Any member of a group that has been negatively stereotyped may experience stereotype threat, regardless of whether or not the group member believes the relevant stereotype (Steele, 1997). Anyone stereotyped as “less than” (e.g., students from historically marginalized groups, women in quantitative fields) may be more prone to belonging uncertainty. This is incredibly relevant information in math class.

In one RCT with Black and White college freshmen, White students were unaffected by a belonging intervention, but Black students were positively affected on multiple measures. The intervention, given in the spring of their freshman year, had astonishingly lasting effects—it reduced the White-Black gap in raw GPA from sophomore-through-senior year by 52%” (Walton & Carr, 2011).

Here’s another incredible finding that’s been replicated across colleges with a large number of (predominately developmental math) students in multiple studies: A single self-report survey question of belonging that was posed in the fourth week of class was the strongest predictor of course completion and, for students who remained in the course, it also strongly predicted whether or not they would receive a sufficient grade for enrollment access to the following math course (Yeager, Bryk, et al., 2013). The question, given on a 5-point scale from always to never, is “When you think about your college, how often, if ever, do you wonder: ‘Maybe I don’t belong here?’” In some studies, the word “college” is replaced with “math class”.

Two additional relevant findings…

In Good, Rattan, & Dweck’s (2012) longitudinal study with calculus students, females who adopted a growth mindset were able to maintain a strong sense of math belonging because it offset the destructiveness of gender stereotypes.

In many belonging interventions, non-stereotyped students are either unaffected or positively affected. In a study by Walton & Cohen (2007), White students in the control group rated their academic fit higher than students in the belonging group; the researchers suggested this could be because White students in the intervention may have experienced a loss of stereotype lift (“the achievement boost that arises from the belief that an out-group is inferior to one’s own”).

Thanks again for your commitment, Brian!

Brian, thank you for this encouragement to those of us who find these conversations daunting, even if we know they are important. I feel like my fear is going too far into the issues I don’t feel equipped to handle. For instance, I teach a first-year course titled Mathematics Through Fiction, where I am desperately trying to build a more inclusive collection of authors in my syllabus, as well as a more honest discussion about what world fiction portrays about mathematics. In doing some more discovery as I fine-tool this year’s reading list, I rediscovered Martin Gardner’s “Against the Odds”, which tells a parable of an African American high school student whose novel interest and talent in mathematics bewilders the racial biases of his ill-prepared high school mathematics teacher. He eventually ends up a Fields medalist thanks to the notice and intervention of his principal, who is a former college classmate of the Stanford mathematics department chair. (That’s a crude, though not inaccurate description; Alex Kasdan’s mathematical fiction website summarizes it better: http://kasmana.people.cofc.edu/MATHFICT/mfview.php?callnumber=mf556). Like much of Gardner, the story feels dated, written “for” the majority-white-male mathematics community, and creates as many stereotypes as it challenges. Still, reading this might open some helpful conversations, and at least it points out that we can use the medium of fiction to question our view of who mathematics is for and who it’s “been for” in the past. I have not decided if the story will become a part of my class, but it did lead me to wonder if any other fiction exists confronting the white supremacist and other non-inclusive legacies of mathematics.

What are your thoughts on Gardner’s story, or using fiction as an entry point to these conversations? I feel as if were my class not about fiction, the genre might discount the importance of the topic at hand. Then again, Flatland’s satire of Victorian society (also in my course’s reading list) is fruitful to this day in understanding and challenging the perspective on women while also raising epistemological and mathematical conversations.

I think it’s great to get to these topics through literature. It can be less threatening and hence simpler to engage when it’s about characters. Assuming everyone has read, and you have an established textual canon with boundaries that focuses the conversation. I often read Ender’s Game with students to talk about intelligence and teaching/learning; in addition, the author (Orson Scott Card) became one of the leading voices in favor of an amendment that defined marriage in my home state, and talking about this hurtful stance in the context of a book that feels progressive usually gets students to think carefully about the text. Last time I read the Harry Potter series, I was focused on what is says about pedagogy, but there is a lot in there that serves as cultural touchstone for our current students about racism, sexism, and socioeconomic status.